August is Women in Translation Month, and that’s going to be my main focus on the blog this month. But Spanish Lit Month has also been extended to August (and expanded to cover Portuguese lit) – so I thought I’d start the month off with a book that falls under both headings.

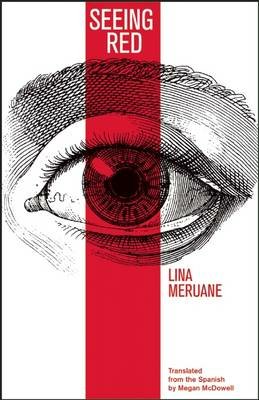

Lina Meruane is a Chilean writer and academic living and working in New York. Seeing Red is her fourth novel, but the first to be translated into English. It’s also semi-autobiographical: Meruane’s protagonist has the same name as her; and the book revolves around a medical condition that the author herself lived with.

It begins at a house party. Lina is on her own in the bedroom when suddenly blood fills her eye: juvenile diabetes had meant that her retinal veins were fragile, and now one has burst. Immediately, Lina starts wondering about the future: is this going to lead to “the dark passage where only anonymous, besieged cries could be heard,” or is there a way out? Lina won’t have any answers until she sees her doctor in a few days, by which time there’s enough blood in her second eye to leave her effectively blind when she moves. The doctor suggests that it may be possible to restore Lina’s sight with an operation – an option she leaps at – but not for another month at least. Much to her consternation, Lina has no choice but to wait.

Naturally, her sudden sight loss affects Lina’s life in many ways. A flavour of some is given in this passage, where Lina has travelled back to Chile on vacation and is met by her father at the airport:

My father comes to the rescue and pulls me out of my introspection. It’s his bony tourniquet hand that falls onto my shoulder. His debilitated skeleton, his long femur I hold onto. He leans over to kiss my forehead and I extend my fingers to run them over his face, trying to trace his face into my palm. I touch him like the professional blind woman I’m becoming. My father is alive, I think, he’s alive in there, inside his body. Then his voice, the word daughter, winds its way through the crush of passengers waiting for suitcases, and in my ear drum his relieved words echo: I had to insist before they’d let me come in and look for you.

(translation by Megan McDowell)

Here we have a clamour of sensory information, as well as a laborious process of working it all out, something that’s increasingly familiar to Lina (that wry “professional blind woman” comment). I’ve quoted at some length here because that’s the nature of the book: each chapter is presented as a single long paragraph. This has the effect of bringing the reader down to Lina’s pace, having to work through situations slowly. It also heightens the sense that there’s no escape from Lina’s circumstances, no short cut to recovery – especially in the sections concerning Lina’s treatment, when it’s unclear whether the operation will work, and she has to take extreme care to avoid causing damage while her eyes heal.

Megan McDowell’s translation is superb, so much rhythm, sound and colour. Here, for example, is Lina in bed with her partner Ignacio:

I started by putting my tongue in a corner of his eyelid, slowly, and as my mouth covered his eyes I felt a savage desire to suck them, hard, to take possession of them on my palate as if they were little eggs or enormous and excited roe, hard, but Ignacio, half-asleep or now half-awake, refused to open them, he refused to give himself to that newly discovered desire, and instead of giving me what I wanted he pushed me back onto the bed and put his tongue in my ear and between my lips although he didn’t dare lick my sick eyes when I asked him to…

That sentence goes on still further, evoking the slow unwinding of Lina’s desire. There are strong feelings throughout Seeing Red, as Lina’s relationships with her loved ones come under strain, and she fixated on the possibility of a cure for her blindness. Strong feelings on the page turn into an intense experience for the reader; a fine English-language debut for Meruane.

Book details

Seeing Red (2012) by Lina Meruane, tr. Megan McDowell (2016), Deep Vellum Publishing, 162 pages, paperback (personal copy).

The UK edition of Seeing Red is published by Atlantic Books.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recent Comments