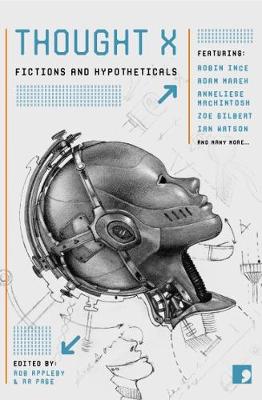

Thought X is the latest anthology in Comma Press’s ‘science-into-fiction’ series, which sees authors paired with scientists to produce a story inspired by a particular idea, with the scientist contributing an afterword that elaborates on the scientific background. (I reviewed a related title, Sara Maitland’s collection Moss Witch, a few years ago.)

The theme for this new anthology is thought experiments. The editors point out in their introduction that there have been contrasting opinions over what exactly constitutes a thought experiment. I am much more of a fiction reader than a scientist (which was certainly brought home to me while reading the book!), so I apologise for any misunderstanding or oversimplification in the review that follows. Essentially, as I understand it, a thought experiment is a scientific ‘what if’ scenario used to highlight a particular question, or a limitation in a theorem. But I can’t resist quoting Terry Pratchett’s definition of a thought experiment, from The Unadulterated Cat: “one which you can’t do, and won’t work”.

I found that, with many of the fourteen stories in Thought X, I hadn’t known about the particular thought experiments beforehand. Now, with the benefit of the afterwords, it’s interesting to see the many different ways in which the writers drew on their thought experiments. In the spirit of placing an artificial structure on something to help describe and explain it, I’m going to organise this review according to how far the different stories refer to their thought experiment directly.

So, first of all, there are stories that don’t mention their thought experiments at all. In ‘The Child in the Lock’ by Robin Ince, Neil has been invited to dinner by his work colleague Tom, and is keen to make the right kind of impression – he’s even bought some new shoes, a pair that Tom. Neil is very early for his train, and goes for a walk to pass the time. He hears some splashing in a nearby lock, and sees the figure of a child. Should he go to the rescue?

The ‘Drowning Child’ scenario (as Prof Glen Newey’s afterword tells me) was put forward by the philosopher Peter Singer as an example of situation where taking the action which most would consider morally right (rescuing the child) would come at a certain cost to the only person nearby (getting wet, and so on). Ince has Neil reluctant to intervene (and ruin his nice new shoes?), then able to rationalise that choice to himself (maybe the kid is diving for coins, or something). The use of short paragraphs in quick succession emphasises the rhetorical dance of Neil’s thought process. The end of the story is suitably chilling.

Hannah, protagonist of Annie Clarkson’s ‘The Rooms’, needs a job. Her brother Alex gets her one at his company, training an artificial intelligence to interact in convincingly human ways. Hannah spends her working day in an enclosed room, across a desk from Myla, a robot in the form of a beautiful woman (there are no requests for male bots in this line of work, Alex tells her). She asks Myla questions on a range of prescribed topics, guiding the bot towards sufficiently ‘woman-like’ responses.

The thought experiment in this case is known as the ‘Chinese Room’, and essentially asks whether a computer carrying out various processes could be capable of understanding what exactly it is doing. Clarkson’s piece likewise asks whether a bot like Myla, simulating the appearance of humanity, could be capable of that. ‘The Rooms’ works well enough on this level alone, but here is where Prof Seth Bullock’s afterword really shines, because it explores the many different ways in which the story reflects its thought experiment: Myla may not understand what she is doing during her sessions with Hannah, but neither does Hannah, really – she just talks, with no sense of how it is affecting Myla. Could it be said that work undertaken in the Rooms is ultimately only of meaning to the client? And so on. I left Bullock’s afterword with a deeper appreciation of Clarkson’s story.

Some stories in Thought X have a discussion of their thought experiment woven in. A powerful example is ‘The Tiniest Atom’ by Sarah Schofield, in which Frank goes to visit the family of his fallen comrade Ted. Frank doesn’t give his name to Ted’s widow Nancy, even saying to her mother: “They call me Ted.” He helps around the garden, and generally makes himself part of the household.

In flashbacks to the trenches, Frank tells Ted about Laplace’s demon: a theory suggesting that the movement of everything in the universe, down to the smallest atom, follows a predetermined path; and that an intellect vast enough to process all that information could then predict the future. Frank had been working on a machine to do just this, and Ted has come to continue the task. Schofield uses the idea of the clockwork universe as a metaphor to explore the emotional displacement caused by the First World War: Frank’s death has created a vacuum; Ted, the outsider with the widest view of this particular ‘universe’, is ideally placed to fill it.

In ‘Red’ by Annie Kirby, Alice wakes one morning to find that her world is black and white – she can no longer perceive colours. A doctor compares her situation to the ‘Mary’s Room’ thought experiment devised by Prof Frank Jackson (who also provides the afterword). Mary lives in an entirely black-and-white room, but through excellent educational resources and intelligence, she has learned everything known to physical science about the world (including the human mind). The question posed by this scenario is: if Mary leaves the room and perceives colour for the first time, does she now gain new knowledge (given that she has studied the science of colour perception)?

Alice concludes that she is actually the opposite of Mary – she had colour perception and then lost it, for a start – but the story of Mary haunts her nonetheless. She dreams repeatedly of Mary, and certain features recur – the colour red, or Mary’s opening question: “What did you bring me?”. As Kirby’s tale unfolds, the theme of hidden (or lost) knowledge becomes key. We see Alice’s relationship with her partner Laurel unravel as Alice loses sight of what brought and held them together. We also see, chillingly, what lies buried in the imagery of those dreams.

Finally, there are stories that place the thought experiment itself at their centre. In ‘Keep It Dark’ by Adam Roberts, scientist Kay and blind theologian Broome travel out to a seemingly abandoned radio telescope, to meet their old colleague Lorenzini, who claims to have solved Olbers’ paradox: that is, in an infinite universe with an infinite number of stars, why doesn’t the night sky blaze with light?

The solution, according to Kay (and confirmed by Prof Sarah Bridle in her afterword) is simply that the universe is not infinite; but Lorenzini is convinced of another answer. He believes that all the light has been swallowed by dark matter, and he will not brook any disagreement. As the story progresses, tensions rise; but Roberts narrates this through Broome’s viewpoint, so one doesn’t ‘see’ exactly what is going on. The reader is left to interpret the meaning of what can be sensed in a world composed mainly of darkness.

Ian Watson’s ‘Monkey Business’ is all about the proposal that an infinite number of monkeys bashing away at typewriter keyboards would eventually produce the text of a Shakespeare play. Watson imagines a simulated world where that experiment plays out. 37 robot monkeys type away in the Templum of the city of Scribe. There are people to check their output for signs of Shakespeare; and whole industries to provide paper, ink, and other resources.

The story follows two characters journeying to Scribe, in order to see the monkeys. Along the way, we discover just how many variables there are in this scenario. Can any of Shakespeare’s plays be typed for the experiment to succeed, or does it have to be a particular one? Does it matter whether or not the capitalisation is correct? What if different monkeys typed out fragments that could be assembled into a complete play? And so on. It’s all told in an enjoyably theatrical style, and illustrates what a pleasure it is to think around with these thought experiments.

Publisher’s competition

Comma Press are currently holding a competition to give away a full set of their ‘science-into-fiction’ anthologies. The full details are here, but essentially you have to tag Comma on Twitter or Instagram with a photo of your copy of Thought X, along with the hashtag #ShareYourThought. The winner will be announced on 21 May.

Book details

Thought X: Fictions and Hypotheticals (2017) ed. Rob Appleby and Ra Page, Comma Press, 260 pages, paperback (review copy).

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recent Comments