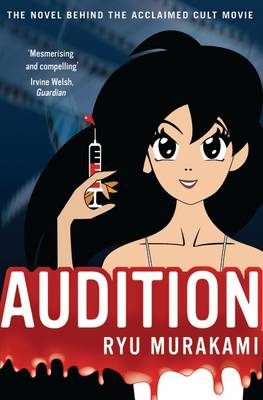

Ryu Murakami, Audition (1997)

Translated from the Japanese by Ralph McCarthy (2009)

I first read the ‘two Murakamis’ a couple of years ago. No doubt I’ll be trying Haruki once more at some point; but Ryu’s book was the one I preferred, so he was the author I was keen to read again sooner. Piercing, my first Ryu Murakami, was a welcome surprise: a novel smart and subtle enough to evade the pitfalls inherent in its premise. Audition promises to be something similar – both are short novels built around a violent confrontation between two damaged individuals. However, although it’s the later book of the two, Audition seems to fall into traps that Piercing managed to avoid.

I first read the ‘two Murakamis’ a couple of years ago. No doubt I’ll be trying Haruki once more at some point; but Ryu’s book was the one I preferred, so he was the author I was keen to read again sooner. Piercing, my first Ryu Murakami, was a welcome surprise: a novel smart and subtle enough to evade the pitfalls inherent in its premise. Audition promises to be something similar – both are short novels built around a violent confrontation between two damaged individuals. However, although it’s the later book of the two, Audition seems to fall into traps that Piercing managed to avoid.

Murakami’s protagonist is Aoyama, who built his fortune making documentaries, but is still haunted by the death of his wife Ryoko seven years previously. In the time since, Aoyama has been able to realise a professional dream of bringing a celebrated German musician to Japan, and made sure to spend quality time with his son Shige; but he’s given no thought to his romantic life – until Shige encourages him to find a new wife.

How to go about it, though? An old work colleague, Yoshikawa, has an idea: hold an audition. Yoshikawa invites potential actresses to audition for a film project (ostensibly based on one of Aoyama’s documentaries, giving him a pretext for being on the interview panel); the film probably won’t get made, but the lucky winner can always be let down gently on that score – and the real prized will, of course, be Aoyama’s hand in marriage. One woman in particular stands out to Aoyama in this process: the beautiful and mysterious Yamasaki Asami – but she may not be quite as innocent as she appears.

Audition spends a good deal of time foreshadowing what is to come, sometimes in very direct terms – for example: “[Aoyama] had no way of knowing the unspeakable horrors that awaited him.” (p. 26). The characterisation is similarly straightforward: Aoyama is fixated on his ideal image of Ryoko, which leads him to become similarly fixated on the vision of perfection that he perceives Asami to be; Asami, for her part, has a troubled past, which leads her to… well, that would be telling. The trouble is that Ralph McCarthy’s translation feels too plain-speaking for this directness to work; there’s not enough of the subtlety which would create the sense of foreboding that the novel is telling us to experience.

Well, okay, let’s leave the build-up to one side. I have no problem in principle with everything hinging on the novel’s final confrontation, as long as that works. It worked in Piercing, but the confrontation there was longer (better able to create tension), and more importantly felt like a contest of equals – two characters who both had the capacity (and the desperation) to do the worst to each other, and no way of guessing who would win out. In those circumstances, it would be quite all right for the characters to appear from thin air, because watching them interact in the moment was powerful enough in its own right.

Audition falls between two stools in this regard: its climactic sequence is too short to generate much momentum on its own, and the characters don’t have enough emotional grounding from what has gone previously in order to substitute for that. Inevitably, there remains a certain amount of interest in finding out exactly how Aoyama’s story will resolve, and a wry ending which points up how absurd the situation has actually become (though it didn’t seem so to the characters involved). But it’s weak sauce, really – especially when I’ve seen much better from Murakami before.

Moving beyond the central narrative, there are some interesting observations elsewhere in Audition; for example, Aoyama watches a marathon, and reflects that his society seems to have become more atomised:

People were infected with the concept that happiness was something outside themselves, and a new and powerful loneliness was born. Mix loneliness with stress and enervation, and all sorts of madness can occur. Anxiety increases, and in order to obliterate the anxiety people turn to extreme sex, violence and even murder. Watching marathon runners on TV back in the day, you got the sense that everyone shared certain fundamental aspirations, but things were different now; it went without saying that each person was running for his or her own private reasons (p. 10).

Passages like this are of course feeding into the novel’s main themes; but they seem too few – and too under-explored – to give Audition the texture that they might. They end up as more of that heavy-handed foreshadowing – reminders of the book Audition could have been.

This review is part of January in Japan, a blog event hosted by Tony’s Reading List. Read my other January in Japan 2015 posts here.

Kawashima Masayuki, the protagonist of Ryu Murakami’s Piercing (translated by Ralph McCarthy), stands over his baby daughter’s crib with an ice pick, testing his resolve not to use it. The full darkness beneath Kawashima’s outwardly happy family life is soon revealed, as we learn that he once stabbed a woman with an ice pick, and he’s afraid he’ll do so again to the baby. He convinces himself that the only way to deal with these feelings is to stab a stranger instead. So he checks into a hotel, calls for a prostitute, and waits.

Kawashima Masayuki, the protagonist of Ryu Murakami’s Piercing (translated by Ralph McCarthy), stands over his baby daughter’s crib with an ice pick, testing his resolve not to use it. The full darkness beneath Kawashima’s outwardly happy family life is soon revealed, as we learn that he once stabbed a woman with an ice pick, and he’s afraid he’ll do so again to the baby. He convinces himself that the only way to deal with these feelings is to stab a stranger instead. So he checks into a hotel, calls for a prostitute, and waits. Where Piercing is short and tight, Natsuo Kirino’s Out (translated by Stephen Snyder) is long and (relatively) roomy, but it shares a focus on individuals at extremes of behaviour. Four women work nights on the production lines of a boxed-lunch factory. In the heat of the moment, one kills her husband, driven to her wit’s end by his abuse. One of her colleagues, Masako Katori, takes charge of disposing of the body, gradually drawing the other women into the secret. Then the pressure is on to keep the killing hidden, from the police and other prying eyes.

Where Piercing is short and tight, Natsuo Kirino’s Out (translated by Stephen Snyder) is long and (relatively) roomy, but it shares a focus on individuals at extremes of behaviour. Four women work nights on the production lines of a boxed-lunch factory. In the heat of the moment, one kills her husband, driven to her wit’s end by his abuse. One of her colleagues, Masako Katori, takes charge of disposing of the body, gradually drawing the other women into the secret. Then the pressure is on to keep the killing hidden, from the police and other prying eyes.

Recent Comments