The Floridian model town of Candor is a picture of wholesomeness, its children impeccably behaved. It’s all thanks to Candor’s founder and mayor, Campbell Banks, and the subliminal Messages that he pumps out underneath the town’s ever-present music. Families pay a hefty fee to move to Candor, but the deal they make if life-long; once you start hearing the Messages, even a single night away from them is fatal, and anyone showing signs of deviance may be subjected to a programme of complete mental reconditioning in the ‘Listening Room’.

The Floridian model town of Candor is a picture of wholesomeness, its children impeccably behaved. It’s all thanks to Candor’s founder and mayor, Campbell Banks, and the subliminal Messages that he pumps out underneath the town’s ever-present music. Families pay a hefty fee to move to Candor, but the deal they make if life-long; once you start hearing the Messages, even a single night away from them is fatal, and anyone showing signs of deviance may be subjected to a programme of complete mental reconditioning in the ‘Listening Room’.

The only kid who knows about the Messages is the mayor’s son, Oscar who has trained himself to resist, and now maintains the pretence of being a perfect child of Candor, whilst covertly arranging escapes from the town (and supplying clients with CDs of his own counter-Messages) . At the start of the novel, Oscar meets Nia Silva, an edgy new arrival in Candor, as yet unaffected by the Messages; he soon becomes attracted to her, and it’s a race against time for him to keep her as she is – not that the attraction is entirely mutual.

I’d characterise Pam Bachorz’s debut as an interesting novel that doesn’t quite live up to its promise. On a narrative level, Candor is efficiently told, and the multiple iterations of will-they/won’t-they are very nicely handled; there’s no shortage of page-turning tension. But what I find missing is a true sense of the strangeness of this place. That narrative efficiency is perhaps a little too efficient to really build up the atmosphere; yes, I felt the chill of what it means to live in Candor at a couple of plot pivots, but it wasn’t there as a constant note in the background.

Similarly, the novel makes some examination of ethics, but it only goes so far. Campbell and Oscar Banks represent two opposing ‘ sides’, but it’s made clear that both have their rights and wrongs – yet I don’t feel the issues these raise are examined as fully as they merit. Campbell is the villain of the piece, and, though we do learn the reasons behind what has done in Candor, it never really prevents him from being unambiguously a bad guy.

This matters less, though, than the case of Oscar, where I think the novel is aiming for a more firmly ambiguous portrait, and doesn’t quite get to the heart of it. Though he is the novel’s narrator and ‘hero’, Oscar is hardly the most sympathetic character, because he is so self-serving. The question is raised of just how much better he is than his father – after all, Oscar is not above manipulating others for his personal gain, and not always with the excuse that he’s helping them escape. Yet, though the question is asked, it’s not explored in detail, and I think that Candor misses out on some depth as a result.

In sum, Candor is a fast read, and a rather engaging debut – a good way to spend a few hours – but it doesn’t truly linger.

Elsewhere

Pam Bachorz’s website

This review is posted in support of ‘women and sf’ week at Torque Control.

Benjamin Obler, Javascotia (2009)

Benjamin Obler, Javascotia (2009) The book I’m reviewing is Salvage by Robert Edric, a novel set one hundred years into the future, when climatic disruption has displaced many and new towns are being built to house them. Edric’s protagonist, Quinn, is an auditor sent to examine the development of one such town; what he finds is, to put it mildly, not encouraging.

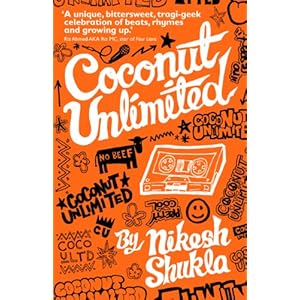

The book I’m reviewing is Salvage by Robert Edric, a novel set one hundred years into the future, when climatic disruption has displaced many and new towns are being built to house them. Edric’s protagonist, Quinn, is an auditor sent to examine the development of one such town; what he finds is, to put it mildly, not encouraging. Nikesh Shukla’s first novel is the story of Amit; he and his friends Anand and Nishant are the only Asian boys at their private school in early 1990s Harrow. They find themselves struggling to be accepted anywhere: their ethnicity marks them out as different at school, and their schooling marks them out as different amongst the other Asian kids in town. The boys find refuge in a shared love of rap, and decide to start their own hip-hop band, which they name Coconut Unlimited (after Amit’s sister, Nish, calls him a coconut – ‘white on the inside, brown on the outside’ [p. 28]). They just need a bit of practice first. Okay, maybe a lot of practice…

Nikesh Shukla’s first novel is the story of Amit; he and his friends Anand and Nishant are the only Asian boys at their private school in early 1990s Harrow. They find themselves struggling to be accepted anywhere: their ethnicity marks them out as different at school, and their schooling marks them out as different amongst the other Asian kids in town. The boys find refuge in a shared love of rap, and decide to start their own hip-hop band, which they name Coconut Unlimited (after Amit’s sister, Nish, calls him a coconut – ‘white on the inside, brown on the outside’ [p. 28]). They just need a bit of practice first. Okay, maybe a lot of practice… Winston Churchill famously described his depression as a “Black Dog”; the premise of Rebecca Hunt’s first novel is that there really was a black dog – Black Pat Chartwell, a six-foot-seven talking dog who walks on his hind legs. The events of Mr Chartwell take place in July 1964, in the week running up to Churchill’s retirement from Westminster (and scant months before his death). Black Pat becomes a lodger in the home of Esther Hammerhans, a clerk in the House of Commons library. Just as Churchill is steeling himself for the end of his parliamentary career, so Esther is watching the calendar with trepidation; the two will come together by novel’s end, and the shadowy figure of Black Pat will never be far away.

Winston Churchill famously described his depression as a “Black Dog”; the premise of Rebecca Hunt’s first novel is that there really was a black dog – Black Pat Chartwell, a six-foot-seven talking dog who walks on his hind legs. The events of Mr Chartwell take place in July 1964, in the week running up to Churchill’s retirement from Westminster (and scant months before his death). Black Pat becomes a lodger in the home of Esther Hammerhans, a clerk in the House of Commons library. Just as Churchill is steeling himself for the end of his parliamentary career, so Esther is watching the calendar with trepidation; the two will come together by novel’s end, and the shadowy figure of Black Pat will never be far away. If you thought Cloud Atlas was a little too conventional, Ultrameta may be the book for you. Trying to interpret (let alone synopsise) Douglas Thompson’s extraordinary first novel is probably a fool’s errand, but let’s see what happens anyway. Subtitled “A Fractal Novel”, Ultrameta is constructed as a series of linked short stories and story-fragments, but exactly how they’re linked is open to debate.

If you thought Cloud Atlas was a little too conventional, Ultrameta may be the book for you. Trying to interpret (let alone synopsise) Douglas Thompson’s extraordinary first novel is probably a fool’s errand, but let’s see what happens anyway. Subtitled “A Fractal Novel”, Ultrameta is constructed as a series of linked short stories and story-fragments, but exactly how they’re linked is open to debate.

They meet at university in London: Anil Mayur is the non-religious son of a wealthy Sikh family from Kenya; his ambition is to be an architect, rather than to take over his father’s business empire. Lina Merali is the daughter of a devout Muslim family from Birmingham, and interested in humanitarian issues. Whatever their differences, these two fall in love; they try their best to keep it a secret, but that can’t last – and life gets only more difficult as the years go by.

They meet at university in London: Anil Mayur is the non-religious son of a wealthy Sikh family from Kenya; his ambition is to be an architect, rather than to take over his father’s business empire. Lina Merali is the daughter of a devout Muslim family from Birmingham, and interested in humanitarian issues. Whatever their differences, these two fall in love; they try their best to keep it a secret, but that can’t last – and life gets only more difficult as the years go by.

Recent Comments