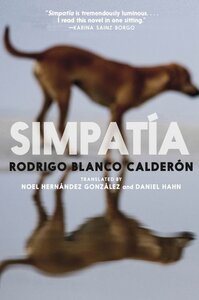

Ulises Kan bonds with his father-in-law, retired general Martín, over a shared love of dogs:

They’d drive [Martín’s dogs] in the pickup to a park just before Cota Mil and let them run loose. Sometimes Martín would get out with them. At other times, he preferred to watch from his seat in the truck, following their comings and goings, the jumping, the barking, the growling, and the biting, as if they were running at some crazy racecourse. Martín would always come back home happy, as if he had won, or lost, a bet against himself.

Translated from Spanish by Noel Hernández González and Daniel Hahn

Ulises decides to get his own dog on the day his wife Paulina leaves Venezuela. Several months later, Martín dies, and Ulises finds that dogs will become even more prominent in his life: Martín has left his house to a foundation for abandoned dogs, and Ulises has been given four months to put everything in place or he’ll lose the apartment he has within the property.

This set-up intrigued me, and the situation only grows more complicated for Ulises. For example, Paulina contests Martín’s will, the house is under watch, and the woman Ulises now loves has her own secrets to keep. At the same time, the country is falling apart in the background, all making for an eventful novel.

Published by Seven Stories Press UK.

Click here to read my other posts on the 2024 International Booker Prize.

Recent Comments