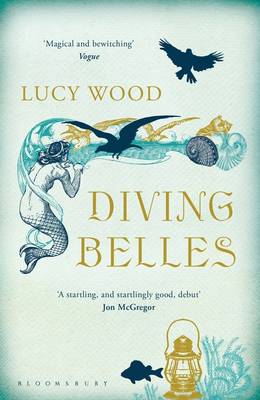

Three years on from her marvellous story collection Diving Belles, Lucy Wood returns with her debut novel. Let’s not beat about the bush: Weathering is just as marvellous. In fact, it had me from the first paragraph:

Three years on from her marvellous story collection Diving Belles, Lucy Wood returns with her debut novel. Let’s not beat about the bush: Weathering is just as marvellous. In fact, it had me from the first paragraph:

Arse over elbow and a mouthful of river. Which she couldn’t spit out. Which soaked in and weighed her down until she was steeped in silt and water, like old tea. But where was her arse anyway, where was her elbow? There was nothing but water as far as she could tell. A stew of water and leaves and small stones and herself all mixed up in it – a strange grey grit. Scattered, then dragged under again, everything teeming, and not sure which way was up or down. Light and dark, light and dark, like a door opening and closing. (p. 1)

I love the rhythm of that prose, and the way it erases the line between character and river. It does so for good reason, too: the character, Pearl, has died; those are her ashes being scattered in the river, apparently still self-aware. They’re being scattered by Pearl’s daughter Ada, who’s returned to the valley to sort out Pearl’s old house; and Ada’s six-year-old daughter Pepper, who never knew Pearl at all. Weathering is the story of how the three generations deal with their sudden change in circumstances.

It’s easy enough to imagine a situation like this being the subject of a straightforward social realist novel – but such a novel would likely have been less interesting and powerful than Weathering. What makes Wood’s book so striking is its sense of what it is to be in that raw landscape. Each of the three protagonists has reason to feel particularly close to the valley: Pearl lived there for years, and of course is now literally part of it. For a wild soul like Pepper, whose life is just beginning, the valley is a place of excitement and colour. For Ada, who thought she’d got away from the valley years ago, it’s dreary and miserable.

Key to Wood’s technique is that she does not allow the valley to become known. For all the vivid descriptions of place, there are no names; this is not somewhere that can be given a label, and thereby given shape. Choppy sentence fragments disrupt the easy flow of understanding; like the characters, we as readers are plunged straight into a new world and have to orient ourselves as best we can.

We can also see this at work in the dialogue, which – like real conversation – is often laden with the unspoken, which can be stifling for Ada, because she finds herself having to be the person others remember, rather than the person she feels she is now; when the village shopkeeper tells her about a collection for ‘old Edwards’, Ada’s emphatic reply of ‘I don’t know who he is’ (p. 35) seems very much like a forlorn attempt to distance herself from the past. As the novel progresses, and Pepper and Ada become more comfortable in their surroundings, so the dialogue and descriptive prose become more conventionally novelistic – but never entirely; the valley will not be tamed.

The title of Weathering has two meanings: being worn away by time, but also holding on, riding out the storm. Ultimately, Wood’s characters experience something of both, as they try to find a place for themselves when the river is the thing that will carry on. Whereas in Diving Belles magic and story lay beneath the surface of everyday life, here it’s the deeper reality of the landscape that pushes through into the characters’ lives.

I want to end with another quotation, which may be tricky, because you really need the momentum of context to understand what Weathering is like. But here’s a stretch of dialogue between Pepper and a woman on the riverbank, which to me captures something of the novel’s general attitude, as well as showing how amusing Wood’s writing can be:

[…]‘It certainly is cold today,’ [Pepper] said.

‘What are you talking about that for?’ The woman said.

Pepper shrugged. ‘I’m trying to make conversation.’

‘Oh,’ the woman said. ‘That.’

‘This is what you have to do. I say, whereabouts do you live and what do you do for a living? And then you tell me. And then I say it’s cold. And then you agree. And then I say I hope the road doesn’t get ice. And then you say you heard the road will get ice. And then I say—‘

‘Christ,’ the woman said. ‘Why do we have to say all that?’

‘I don’t know,’ Pepper said. (p. 108)

Why indeed? Weathering is a novel that says just what it needs to say, in its own idiosyncratic fashion. It cements Lucy Wood’s voice as one that will continue to have my full attention.

Elsewhere

Weathering has been picking up very positive mentions all over the place; here are a few of them:

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recent Comments