Here’s another round-up of some of the books I’ve read lately.

Christopher Priest, The Adjacent (2013)

If there’s one thing you can be sure of with a Christopher Priest novel (and that’s quite an ‘if’), it is that the spaces between what is told will be at least as important as the tale itself. That was certainly true of 2011’s The Islanders, whose gazetteer-like structure left readers with a set of pieces from which multiple narratives could be constructed.

If there’s one thing you can be sure of with a Christopher Priest novel (and that’s quite an ‘if’), it is that the spaces between what is told will be at least as important as the tale itself. That was certainly true of 2011’s The Islanders, whose gazetteer-like structure left readers with a set of pieces from which multiple narratives could be constructed.

The Adjacent begins with photographer Tibor Tarent returning to what is now the Islamic Republic of Great Britain from a war zone where his partner Melanie, a doctor, was caught in the blast from an adjacency weapon, a device which annihilates everything within its triangular field. He has been summoned by the government, who are keen to learn what he knows of one Thijs Rietveld, the Dutch scientist who invented adjacency technology; Tarent insists he’s never heard of the man – though that assertion would seem to be contradicted by a later chapter. It transpires that an adjacency weapon has wiped out a large area of West London; so much for Rietveld’s certainty that his technology could never been used in aggression.

The novel returns to Tarent periodically, but also takes in the First and Second World Wars, and Priest’s own fictional world of the Dream Archipelago; in these times and places, we meet individuals who may be analogues of Tarent and Melanie (and perhaps other characters besides). We learn that adjacency technology works by shifting matter into an adjacent quantum universe – though it evidently does a lot more than that.

The characters of The Adjacent do not always feel fully rounded, which in turn has a detrimental effect on the power of the novel’s love story. But there is still much to enjoy here, in how Priest paints with realities that bleed into each other and fray at the edges. There’s a wonderful recurring image of flight as freedom, the Spitfire used not to make war, but to transcend it. This gives rise to a sequence towards novel’s end which is one of the most affecting passages of imaginative writing I have read in a long time. Priest casts the fantastic into shapes that no one else does, and The Adjacent is a fine demonstration.

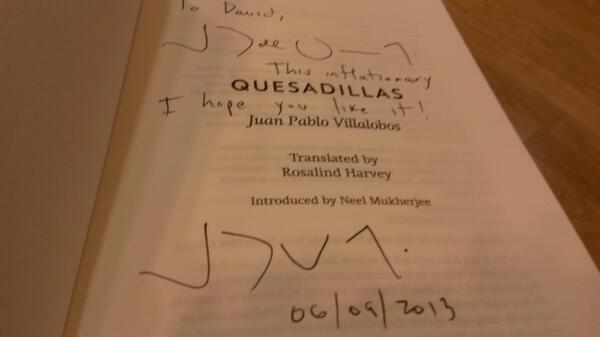

Juan Pablo Villalobos, Quesadillas (2012)

Translated from the Spanish by Rosalind Harvey, 2013

And Other Stories return to where they started with a second title from Juan Pablo Villalobos, author of the superb Down the Rabbit Hole. Quesadillas shares the earlier book’s wry wit and cutting absurdity. We meet Orestes, one of seven children (all named after characters from Greek mythology) living in the family home on a remote Mexican hill. Orestes would dearly love to escape, but his siblings seem to have better luck on that front than he does.

What makes the novel work so well for me is how the wider political and economic upheavals in the background are filtered through Orestes’ home life – so the quesadillas that his mother makes become more or less substantial as fortune allows; his household comes under pressure from the rich family who build a big house next door; and so on. As the pages turn, reality stretches further, until the family are literally defending their home. Add to this some sharp lines (‘Basically, all the rebels did was shout “Long live Christ the king!” and pray for time to go back to the beginning of the twentieth century’, p. 22) and you have a book that’s very much worth reading.

John Williams, Stoner (1965)

The Vintage Classics edition of this novel really seems to have taken off in the UK these last few months; I wasn’t too surprised to see that it was the next choice for one of my book groups. It chronicles the life of one William Stoner, who is born into a Missouri farming family, but ends up a professor of literature. After his death, Stoner is not much remembered, let alone celebrated; John Williams then explores the quiet dramas that make up such an ‘ordinary’ life.

The Vintage Classics edition of this novel really seems to have taken off in the UK these last few months; I wasn’t too surprised to see that it was the next choice for one of my book groups. It chronicles the life of one William Stoner, who is born into a Missouri farming family, but ends up a professor of literature. After his death, Stoner is not much remembered, let alone celebrated; John Williams then explores the quiet dramas that make up such an ‘ordinary’ life.

I feel ambivalent towards Stoner, and think Scott Pack has it about right. The novel has some very good aspects: I especially like Williams’s evocation of the grit and graft of the farm; and the running theme of domestic and professional spaces being used as the battlegrounds for control in Stoner’s life. But Williams gives his female characters short shrift (to put it mildly); and, for me, there’s too little sense of friction – Stoner lets life sweep him along to such a degree that I find it working against the emotion and drama. There are a few times when Stoner’s strength of conviction does come to the fore, and they are some of the book’s most compelling moments; but I wish they weren’t so few and far between.

A.M. Homes, May We Be Forgiven (2012)

This was my other book group’s latest choice; I liked it better than Stoner, but still have my reservations. I didn’t know much about A.M. Homes’s work beforehand, but I was anticipating a darkly humorous twist on the Great American Novel, which is pretty much what I got. What I’m unsure about is whether May We Be Forgiven subverts the archetype enough for my liking.

At the start of the novel. George Silver causes a fatal road crash and later smashes a beside lamp over his wife Jane’s head, killing her. He’s then sent away to a psychiatric institution, which leaves his brother Harry having to move in to look after George’s and Jane’s children. Harry’s wife Claire leaves him because he was having an affair with Jane – and so Harry’s run of misfortune continues, to a sometimes-absurd degree. There are certainly parts of May We Be Forgiven which I found amusing, such as the late of blooming of Harry’s ninety-year-old mother, who suddenly gets into dancing and all kinds of other activities. It often seems as though Harry is surrounded by people who are in command of the stories of their own lives, and the novel reveals how he tries to take control of his.

Looking back, I can’t quite put my finger on the reason I didn’t enjoy May We Be Forgiven More. I do know that the book group discussion made me feel like reading it again, to see what I’d missed. Maybe the time will be right, another day.

Peter Mattei, The Deep Whatsis (2013)

The spine of this novel reads: ‘The Deep Whatsis by Peter Mattei is the bastard love-child of Bret Easton Ellis and Chuck Palahniuk. Eric Nye is a character you’ll either love or hate. Probably hate.” Well, I feel somewhere in between the two extremes towards him, so there.

The spine of this novel reads: ‘The Deep Whatsis by Peter Mattei is the bastard love-child of Bret Easton Ellis and Chuck Palahniuk. Eric Nye is a character you’ll either love or hate. Probably hate.” Well, I feel somewhere in between the two extremes towards him, so there.

Eric Nye is an ad agency’s ‘Chief Idea Officer’, who takes delight in his job of weeding out people to be fired; seemingly can’t look at a woman without objectifying her; and is about to find out that the pretty young intern with whom he’s just had a one night stand is not going away any time soon. So far, so unpleasant; and Nye stays that way for much of the book – but there is a relentless rhythm to his narration that keeps one going.

The novel’s satire of advertising and corporate culture feels a little too over-familiar truly to bite; but, further in, Nye’s subjectivity is challenged – there are hints that he may have done things he cannot remember – and this is what really captured my interest. Nye’s view of the world is all to him, so when its integrity is called into question, that hits him more than talk of morals or ethics ever could. Nye doesn’t quite become a reformed character, but he does start to change his mind; and his narration becomes a little less self-assured as a result. He’s not quite likeable, but we do start to see the person he could be. I’m struck by Mattei’s skilled control of language in The Deep Whatsis, and I’d certainly look forward to reading more of his work.

Like this:

Like Loading...

The evening was hosted by the excellent And Other Stories press, as publisher Stefan Tobler interviewed Juan Pablo Villalobos, the Mexican author of Down the Rabbit Hole (which I reviewed here) and Quesadillas (which I reviewed here). We began with Villalobos reading from the opening of Quesadillas, first in Spanish (cue laughter from the Spanish-speakers in the audience and those of us who’d already read the book in English and know what the beginning is like), then English (cue laughter from everyone else). Tobler then read from another And Other Stories title, Rodrigo de Souza Leão’s All Dogs are Blue (which I reviewed here), which Villalobos has translated into Spanish from the original Portugese. Both readings underlined how much these books are spoken texts.

The evening was hosted by the excellent And Other Stories press, as publisher Stefan Tobler interviewed Juan Pablo Villalobos, the Mexican author of Down the Rabbit Hole (which I reviewed here) and Quesadillas (which I reviewed here). We began with Villalobos reading from the opening of Quesadillas, first in Spanish (cue laughter from the Spanish-speakers in the audience and those of us who’d already read the book in English and know what the beginning is like), then English (cue laughter from everyone else). Tobler then read from another And Other Stories title, Rodrigo de Souza Leão’s All Dogs are Blue (which I reviewed here), which Villalobos has translated into Spanish from the original Portugese. Both readings underlined how much these books are spoken texts.

If there’s one thing you can be sure of with a

If there’s one thing you can be sure of with a  The Vintage Classics edition of this novel really seems to have taken off in the UK these last few months; I wasn’t too surprised to see that it was the next choice for one of my book groups. It chronicles the life of one William Stoner, who is born into a Missouri farming family, but ends up a professor of literature. After his death, Stoner is not much remembered, let alone celebrated; John Williams then explores the quiet dramas that make up such an ‘ordinary’ life.

The Vintage Classics edition of this novel really seems to have taken off in the UK these last few months; I wasn’t too surprised to see that it was the next choice for one of my book groups. It chronicles the life of one William Stoner, who is born into a Missouri farming family, but ends up a professor of literature. After his death, Stoner is not much remembered, let alone celebrated; John Williams then explores the quiet dramas that make up such an ‘ordinary’ life.

The spine of this novel reads: ‘The Deep Whatsis by Peter Mattei is the bastard love-child of Bret Easton Ellis and Chuck Palahniuk. Eric Nye is a character you’ll either love or hate. Probably hate.” Well, I feel somewhere in between the two extremes towards him, so there.

The spine of this novel reads: ‘The Deep Whatsis by Peter Mattei is the bastard love-child of Bret Easton Ellis and Chuck Palahniuk. Eric Nye is a character you’ll either love or hate. Probably hate.” Well, I feel somewhere in between the two extremes towards him, so there. If you lost part of yourself, what would you become? What if you didn’t even know what you had to lose?

If you lost part of yourself, what would you become? What if you didn’t even know what you had to lose?  The characters in The Tiny Wife lost parts of their selves in a single event, but it’s the continual harshness of her life that has taken its toll on Rue, the protagonist of

The characters in The Tiny Wife lost parts of their selves in a single event, but it’s the continual harshness of her life that has taken its toll on Rue, the protagonist of  There’s nothing fantastical in

There’s nothing fantastical in

Recent Comments