My latest review at The Zone is of Jesse Bullington‘s interesting-but-flawed medieval fantasy The Sad Tale of the Brothers Grossbart. This tells the story of twin graverobbers who have run-ins with various entities, both natural and otherwise, on their travels. When magic intersects with the narrative, the results are fascinating; at other times, the novel doesn’t work quite so well.

My latest review at The Zone is of Jesse Bullington‘s interesting-but-flawed medieval fantasy The Sad Tale of the Brothers Grossbart. This tells the story of twin graverobbers who have run-ins with various entities, both natural and otherwise, on their travels. When magic intersects with the narrative, the results are fascinating; at other times, the novel doesn’t work quite so well.

Tag: fantasy

Finch (2009) by Jeff VanderMeer

In his latest novel, Jeff VanderMeer brings us a mystery in which Detective John Finch — whose name is not John Finch, and who isn’t a detective (or so he keeps telling himself) — investigates a double murder. One of the victims is a man who can’t possibly be a murder victim, whilst the other is a gray cap—

In his latest novel, Jeff VanderMeer brings us a mystery in which Detective John Finch — whose name is not John Finch, and who isn’t a detective (or so he keeps telling himself) — investigates a double murder. One of the victims is a man who can’t possibly be a murder victim, whilst the other is a gray cap—

If the term ‘gray cap’ is unfamiliar (and even if it’s not!), welcome to Ambergris, the setting of VanderMeer’s City of Saints and Madmen (2003) and Shriek: an Afterword (2006), which, together with Finch, form a cycle of novels – though it’s not necessary to have read the previous two (and I’d say Finch makes a pretty good entry point). I am in the awkward position of remembering enough about City and Shriek that I didn’t come to the new book cold, whilst having forgotten enough that I know I missed some things in Finch, and can’t really give a proper assessment of the Ambergris Cycle as a whole. That’s where I started from, anyway.

Finch is set a hundred years after Shriek, at a time when Ambergris has been taken over by the gray caps, the inscrutable fungoid people who previously lived beneath the city. Spores that could do who-knows-what (or who-dares-imagine) to you proliferate, such that it’s a bad idea to go around barefoot, because you never know what you’ll step on. Some of the human population are held in camps, others kept docile with fungal drugs; but there are those who’ve their lot in with the gray caps to become half-human, half-mushroom ‘Partials’ – and there are rebels, led by the mysterious Lady in Blue, though she hasn’t been heard of for six years. And there are those like John Finch, a human in the employ of the gray caps, just trying to make their way through this world as best they can.

And these are difficult waters to navigate because, as in any good mystery, there are secrets, deceptions, and masks aplenty in Finch, not least those of the protagonist himself. ‘John Finch’ is an identity he created to hide that of the person he was before the Rising of the gray caps; and, despite his profession, Finch still doesn’t feel comfortable thinking of himself as a detective. To be fair, he doesn’t get very far with actual detecting in the novel, as most of the other characters seem to know more than he does, and are keen to reveal their knowledge to Finch only on their terms, not his. The motives and intentions of the gray caps are as mysterious as ever… all of this keeps the pages turning, no question.

Something else that keeps the pages turning is VanderMeer’s compelling prose. The style of an Ambergris story has always been significant, and Finch continues that trend. This novel is written in spiky, clipped prose that often gives an impression of restlessness, of wanting to get on to the next bit. For instance:

Inside, a tall, pale man stood halfway down the hall, staring into a doorway. Beyond him, a dark room. A worn bed. White sheets dull in the shadow. Didn’t look like anyone had slept there in months. Dusty floor…

This noir-inflected idiom is in sharp contrast to the lush, flowing styles I’ve associated with previous Ambergris books; but of course it’s entirely appropriate to the setting: Ambergris is a meaner, grimmer place than it was, so the voice that tells its stories naturally has a harder edge. VanderMeer’s writing is still vivid and striking (such as his idea of the ‘memory hole’, a revolting, organic way of delivering messages), but the colours of his palette are subtly different in Finch; for example, there’s more action this time around (or it’s more prominent than it was) – and it’s very effective action at that.

VanderMeer’s style in Finch also makes the telling feel more direct, which is something of a double-edged sword. On one hand, this novel is revealing things about the nature of Ambergris that the first two kept hidden, and the style plays into that aim. On the other hand, I can’t help feeling that some of the otherworldliness is lost, that some of these extraordinary revelations become a little too matter-of-fact in the telling. I also can’t help wondering if the pace is just that bit too brisk, resulting in a similar effect.

The characterisation of John Finch is another aspect about which I have reservations. In a very real sense, we don’t know Finch; and he’s often acted upon rather than being the actor himself. These can make it hard to see him as an individual, and I don’t think that VanderMeer always manages to overcome that. When he does, though, it makes for some powerful moments. For example, there’s the time when Finch is pleading with his lover, Sintra, to tell him something about herself – not out of idle curiosity, but because he’s desperate for something in his life to be real, and he wishes it were her. At times like this, one feels the burden of living in a world of secrecy.

In the end, then, I don’t think that Finch is entirely successful; but it is an interesting – and gripping – fusion of noir and fantasy. It takes unexpected turns, and ends at a point that may seem too early in some ways, but is actually quite appropriate – because it’s the point at which the story of Finch can no longer be told, and the style of Finch can no longer tell its story. But Jeff VanderMeer can go on telling his stories; and I hope he does, because they’re like no one else’s.

Robert Holdstock, 1948-2009

Very sad news: as reported by David Langford, Robert Holdstock, author of the World Fantasy Award-winning Mythago Wood, has died at the age of 61. I’ve read only a couple of his books, but enjoyed them venry much; and, when I met him briefly at one Fantasycon, he was as friendly a person as he was good a writer. This is a sad day for literature in general, and the fantasy field in particular.

Stairway to Hell (2009) by Charlie Williams: The Zone review

Now up at The Zone is my review of Charlie Williams‘s latest novel, Stairway to Hell. It’s a tale of the occult, soul-swapping, and a pub singer who believes his own (self-)publicity. Quite fun.

Now up at The Zone is my review of Charlie Williams‘s latest novel, Stairway to Hell. It’s a tale of the occult, soul-swapping, and a pub singer who believes his own (self-)publicity. Quite fun.

In This Way I Was Saved (2009) by Brian DeLeeuw

In his début novel, Brian DeLeeuw brings us a story about two boys. One of the boys is real, while the other isn’t – but you may have a hard time deciding which is which. Our narrator is Daniel, who met Luke in the playground, when the latter was six. Luke is the only person who can see him; yet Daniel seems no common-or-garden ‘imaginary friend’, having apparently attained consciousness. Daniel returns home with Luke, to find a household under strain: Luke’s mother, Claire, is fragile, still affected by her own mother’s suicide; when an incident brings matters to a head, she leaves, taking Luke with her.

In his début novel, Brian DeLeeuw brings us a story about two boys. One of the boys is real, while the other isn’t – but you may have a hard time deciding which is which. Our narrator is Daniel, who met Luke in the playground, when the latter was six. Luke is the only person who can see him; yet Daniel seems no common-or-garden ‘imaginary friend’, having apparently attained consciousness. Daniel returns home with Luke, to find a household under strain: Luke’s mother, Claire, is fragile, still affected by her own mother’s suicide; when an incident brings matters to a head, she leaves, taking Luke with her.

One day, Claire has a surprise for Luke – she’s bought him a pet dog. This new friend starts to take Daniel’s place in Luke’s life, so much so that Daniel finds his very self disintegrating. In a bid for survival, Daniel tricks Luke into poisoning the dog with some of Claire’s medication. She, of course, doesn’t believe her son when he says that Daniel told him to do it, and takes Luke to see a psychiatrist. Soon after, Luke is able to restrain Daniel, eventually locking him away inside his head, for twelve whole years. But, when Luke is eighteen, Daniel re-emerges – with his own ideas of what Luke should do, who Luke should be.

In This Way I Was Saved is quite a difficult book to evaluate. How do you judge characterisation, for example, when you can’t even trust that the narrator is – well, is, full stop? Well, let’s see: DeLeeuw has created a chilling presence in Daniel, a narrator who’s just that bit too knowing, whose voice is that bit too articulate. Not to mention that his opinions are also pretty vile; Daniel has little patience for humans and their messy emotions: when Luke finds a girl in whose company he can relax and forget his cares, Daniel just takes the view that Luke is being insincere – and the situation Daniel then engineers is not a pleasant one. As a portrait of such a cold individual, the book is a great success.

Yet there’s ambiguity here, too, as it’s possible to read Daniel as being entirely a product of Luke’s delusion. This is a more difficult reading to make, because the narration naturally invites us to view Daniel as a separate entity; and I’m not sure that the novel sustains its ambiguity through to the end. But it’s fascinating to read a scene and see it happening in two different ways simultaneously; DeLeeuw interweaves the possibilities well. The reading of Daniel-as-delusion also deepens the book’s portrait of people and lives unravelling; it’s harrowing for characters and readers alike.

In This Way I Was Saved is not without its flaws. I feel a sense of distance in the progression of the plot – as though it’s happening rather than being made to happen – which I think arises because neither Luke nor Daniel is able to truly drive the story directly. Nevertheless, I am impressed with what DeLeeuw has done in his novel. It’s easy to assume, from the first few pages, that you know who Daniel is and what has happened. I read most of the book thinking, it can’t be that simple – and, happily, it’s not.

No more of that, though, for it’s the road to spoilers. To conclude: In This Way I Was Saved is an intriguing puzzle of a book which takes you into a mind that’s not a comfortable place to visit, but that visit is compelling all the same. Whose mind is it, though? There’s a question to ponder…

Ransom (2009) by David Malouf

This is where I start from: David Malouf’s name was unknown to me before I received the review copy of Ransom, but I gather now that he is one of Australia’s most acclaimed writers. The novel (Malouf’s first in ten years) draws on Homer’s Iliad, which I’ve never read; and the Trojan War is one of the aspects of Greek mythology that I don’t know much about. In short, I came to Ransom largely from a position of ignorance, which means I’ve probably missed a lot of the book’s subtleties – but let’s see what I can take from it all the same.

This is where I start from: David Malouf’s name was unknown to me before I received the review copy of Ransom, but I gather now that he is one of Australia’s most acclaimed writers. The novel (Malouf’s first in ten years) draws on Homer’s Iliad, which I’ve never read; and the Trojan War is one of the aspects of Greek mythology that I don’t know much about. In short, I came to Ransom largely from a position of ignorance, which means I’ve probably missed a lot of the book’s subtleties – but let’s see what I can take from it all the same.

As Ransom begins, Achilles’ friend and comrade-in-arms Petroclus has been killed by Hector, the son of King Priam of Troy. Achilles takes his revenge on Hector and, attempting to assuage his grief, parades the body repeatedly before the city of Troy. Seeing this display, Priam first interprets it as a sign that the gods are mocking him. But then a vision shows him another way that things could be, and Priam resolves to travel in disguise to Achilles, taking a cart full of treasure with which to ransom Hector’s body.

In his afterword, Malouf comments that ‘[Ransom]’s primary interest is in storytelling itself – why stories are told and why we need to hear them, how stories get changed in the telling’. I’m generally wary of author statements like this, because I prefer the text to speak for itself, and allow me to draw my own conclusions. And I find that the theme of storytelling is not what stands out the most in Ransom; yes, it’s mentioned, but I don’t see that it is really being explored to such an extent (of course, it may well just be that I’m missing out on the interplay between novel and Iliad).

What I take away the most from Ransom is the portrait of a world which is not my own. I haven’t the knowledge to judge how authentic is Malouf’s depiction of ancient times (and it’s a legendary version, anyway), but it’s convincing enough for me. This is a society to which the idea of things happening by chance is an alien concept, where everyone is bound to the stations given them by the gods, even a king: he must be seen to be a king, becoming more ‘object’ than individual – which is why Priam’s plan to disguise himself causes such controversy. It takes some effort to connect with this world that thinks so differently, and so it should – but the reward is a fully immersive tale.

Although Ransom never comes across as pastiche, Malouf’s prose does give it a legendary quality; it feels at one and the same time as if the novel is taking place in the ancient world as it might have been (incidentally, Ransom is an excellent example of how to integrate historical detail without drowning the narrative), and in a timeless ‘land of fable’. It’s a singular reading experience, which is worth a look.

(This review was first published on BookRabbit.com)

The Manual of Detection (2009) by Jedediah Berry

I wouldn’t normally dwell on the book-as-object, but I have to say that The Manual of Detection is one of the most attractive volumes that I’ve seen in quite some time. You can’t see from the picture, but it has a laminate cover (i.e. the image is printed directly on to the cover, with no dust-jacket); and the whole package gives the impression of a book that has been designed with great care and attention. Furthermore, it has been made to resemble the fictional Manual of Detection described in the novel; opening the book is an invitation to step into its own unique world.

I wouldn’t normally dwell on the book-as-object, but I have to say that The Manual of Detection is one of the most attractive volumes that I’ve seen in quite some time. You can’t see from the picture, but it has a laminate cover (i.e. the image is printed directly on to the cover, with no dust-jacket); and the whole package gives the impression of a book that has been designed with great care and attention. Furthermore, it has been made to resemble the fictional Manual of Detection described in the novel; opening the book is an invitation to step into its own unique world.

And the text itself makes good on that invitation; what strikes me most about The Manual of Detection is the way that Jedediah Berry has woven his fictional world together. The setting is an unnamed city in which a thousand noir stories have taken place, crimes solved by the behatted, cigar-chomping detectives of the Agency, the greatest of whom is Travis T. Sivart. Now Sivart has gone missing, and his clerk, Charles Unwin, has been promoted in his stead. Convinced that this is an error, Unwin goes upstairs to the office of Edward Lamech, Sivart’s ‘watcher’ and the author of the memo apparently granting this promotion — only to find Lamech’s dead body sitting behind the desk. Unwin sets out to find Sivart; and, of course, it all gets more complicated from there…

Berry’s creation is fascinating, and his novel transporting in the truest sense, in that it takes one out of the real world, and into a sideways reality that convinces as a functioning world within the covers of the book, even as one acknowledges that it couldn’t function if it actually existed. The Agency itself is a huge, sprawling organisation whose absurd bureaucracy is a delight to imagine: the different categories of staff are so segregated that there are underclerks in the archive who don’t even know what a detective is. And consider the thoughts it engenders in Unwin as he makes his way to Lamech’s office:

Imagine the report he would have to write to explain his actions: the addenda and codicils, the footnotes, the footnotes to footnotes. The more Unwin fed that report, the greater would grow its demands, until stacks of paper massed into walls, corridors: a devouring labyrinth with Unwin at its center, spools of exhausted typewriter ribbon piled all around.

(Incidentally — or perhaps not — I think that quotation also demonstrates Berry’s considerable flair for writing prose.)

The Manual of Detection is set in a world where detectives’ cases get pulpish nicknames like ‘The Oldest Murdered Man’ or ‘The Man Who Stole November Twelfth’, and sound equally outlandish in synopsis; where bizarre things happen, such as Charles Unwin encountering a man who is apparently relaying Unwin’s every move down the telephone, before the following exchange takes place:

“Were you speaking about me just then?” Unwin asked.

The man said into the receiver, “He wants to know if I was speaking about him just then.” He listened and nodded some more, then said to Unwin, “No, I wasn’t speaking about you.”

Yet all has a perfectly rational explanation — rational within the terms of the novel, anyway. There’s less fantastication than that comment might suggest, but a little goes a long way in this case. I’m being deliberately vague about the details, because so much of the joy of reading The Manual of Detection lies in the discovery of what happens. But I will say that the final third takes a different tack as the threads of story come together; and I feel it sits quite awkwardly with the rest (then again, I did struggle to follow the plot a bit at this point, so it could just be that).

Criticisms aside, though, what I’ll take away from The Manual of Detection is the singular experience of reading it, its distinctive feel and atmosphere — and I’ll be mightily intrigued to see what Jedediah Berry does next.

Finding Emmaus (2009) by Pamela S.K. Glasner

Finding Emmaus is a beginning. On a prosaic level, it’s the first volume in Pamela Glasner’s ‘Lodestarre’ series; but, more than this, the entire movement of the story is towards putting the pieces in place which (one assumes) will be played out in the rest of the series. The build-up is decent enough, but it leaves the book in an awkward position, as it feels to me that the most interesting stuff is yet to come.

Finding Emmaus is a beginning. On a prosaic level, it’s the first volume in Pamela Glasner’s ‘Lodestarre’ series; but, more than this, the entire movement of the story is towards putting the pieces in place which (one assumes) will be played out in the rest of the series. The build-up is decent enough, but it leaves the book in an awkward position, as it feels to me that the most interesting stuff is yet to come.

The central conceit of Finding Emmaus is the existence of ‘Empathy’, a suite of psychic abilities (including, but not limited to, that of experiencing the feelings of others) which have been mistaken over the centuries for mental illness. Two narratives alternate: the first is the life-story of Francis Nettleton, an early settler of Conneticut. Tragedy stalks Frank’s life as he discovers his Empathic abilities; but he resolves as an adult to learn all he can about Empathy, and compile a ‘guidebook’ to the subject (which text he calls The Lodestarre). The second narrative is set in the present day, and follows Katherine Spencer; a parapsychologist friend suggests that her ‘bipolar disorder’ (which hasn’t responded to treatment) may actually be Empathy, and Katherine embarks on a journey in search of Frank Nettleton’s old house, Emmaus – and the lost manuscript of The Lodestarre.

The biggest problem with the novel, I find, is a lack of true involvement at the deeper level of the prose. For example, there’s a scene depicting a powerful sermon – but the preacher’s charisma stays on the page. We hear a lot about what Empathy is, what it involves… but I can’t say that the prose evoked for me a sense of what it feels like. There are other examples, but I think these suffice to illustrate my point: generally speaking, the words don’t do enough to create the affect of what they describe. There are some places where Glasner’s prose does work well – an early passage where Katherine hears an intruder in her house builds tension nicely, for example; and the book’s closing sentences stir the emotions – but they are too much the exception rather than the rule.

Another issue with Finding Emmaus is an awkwardness of structure. The alternation of Frank’s and Katherine’s stories sets up a nice rhythm for the novel; but, after Katherine finds the Lodestarre manuscript, the book changes gear – relationships change, and the issue of mistreatment of those deemed mentally ill (which has been bubbling under throughout) comes strongly to the fore. But all this is done rather too quickly, in a way that seems artificial and draws too much attention to itself, lessening the impact of this section.

The title of the novel doesn’t just refer to Frank’s house; to Katherine, Emmaus represents ‘shelter from the storm’ – a place where she can feel safe as an Empath and perhaps, by book’s end, a bastion against the coming storm… But to continue down that path would be to move beyond the present volume. And there’s the rub because, going back to what I said earlier, the present volume feels too much like the prelude to the main event – which is fine for the next book in the series, but less so for this one. Yes, Finding Emmaus is a beginning; but I wish it were a better whole.

Two Stories: Tim Pratt

It’s occurred to me that, if I’m going to do the occasional random short fiction review (as I did yesterday), it might be more interesting to cover two stories at once, to give a point of comparison. So let’s try that, and see how it goes. The author I’ve chosen today is Tim Pratt, whom I’d heard good things about but never actually read – though I’ve had a story collection of his on my shelves for several months, and really must get around to reading it.

Anyway, the first story I’m covering in this review is ‘A Programmatic Approach to Perfect Happiness’ (2009), published in Futurismic. The story is described by the site’s Pail Raven in his introduction as ‘a little Gonzo, a little retro, but all Tim Pratt’. I can’t really judge the last of those yet (though I suspect, and hope, that it’s true), but the first two are definitely right.

This is a robot story that has an air of old-school science fiction about it, but not in a way that comes across as a tired retread or too-knowing pastiche; it’s more that Pratt knows the area in which he’s writing, and uses its history and conventions as a way in to the story he wants to tell. Our narrator is Kirby, a sentient android who has married a human woman, April. Essentially, the tale is a portrait of familial (and extra-familial) relationships, though there are also mysterious ‘emotional viruses’ in the background (April’s daughter Wynter, usually a moody goth, has contracted a virus that makes her happy – which explains why she’s being unusually civil towards Kirby).

What I like about this story is that it’s deceptively light: it’s humorous, but searching questions are being asked underneath humour. I’ll quote a passage which illustrates both of these points (context: Wynter has just explained to Kirby why she is often difficult with him:

“I understand.” I do. Like most of my kind, I am exceptionally good at running theoretical models of human interior experience, and of constructing self-coherent theories of mind.

There’s humour here in the incongruity between the typical human platitude and Kirby’s robotic literalness (I should add that the over-formal diction Pratt uses for Kirby’s voice is just right); but deeper issues are being explored here: is a model constructed inside a sentient computer truly equivalent to human feelings? There’s more elsewhere in the story: if a robot like Kirby can reprogram himself to feel anything he wants, is a robot emotion equivalent (or less genuine? or more?) than a human one, caused by chemical changes in the brain? Then there are the ethical dilemmas, which I won’t get into, because it would spoil the story for you. Go and have a read.

The second Pratt story I read (I should say, I chose these more-or-less at random) is ‘Her Voice in a Bottle’ (2009) from Subterranean magazine. This is a very different tale from the previous one – more serious in tone, magical realist rather than science fiction – but I can see common characteristics: playfulness and seriousness combined, and a sense of putting a well-worn theme to work. I still haven’t made up my mind about the story – not about whether I like it (I do), but about whether it pushes its luck too far.

You see, the protagonist is a fictionalised version of Pratt himself, yet the story purports to be ‘filled with true stories of my life’ (I say ‘purports’ because I have no way to judge how far that’s true), whilst acknowledging and reflecting upon its own fictitiousness. I’m wondering if the piece is too self-referential for its own good… on balance, it probably isn’t, otherwise I wouldn’t be asking myself the question! And, to be fair, the metafictionality (is that even a word?) is integral to the project of the story.

So, we have our protagonist, Tim (for the sake of clarity, I’ll refer to the character as ‘Tim’ and the author as ‘Pratt’), who tells us about his ex-girlfriend, Meredith, who flits in and out of his life like a recurring dream. I use that phrase quite deliberately: she is apparently able to appear and disappear at will; no one other than Tim actually ever meets her; and nothing else is quite as real to him when he’s in her presence.

All this leads naturally to the assumption that Meredith is a product of Tim’s imagination, made flesh only in his own mind; but Pratt knows this, and addresses it directly – coming to the conclusion (as I read it) that whether Meredith is real or not makes no difference, because the effect she has is the same either way. ‘Her Voice in a Bottle’ evokes a kind of young love that’s like a whirlwind, that seems more vivid in later years than it probably (but who can say?) than it was at the time; and the story asks, would you want to return and find out what it was really like, or are you content with your memories, inaccurate though they may be? A fascinating, thoughtful piece. Go and have a read of this one, too.

These two stories are very different, but I found both to be equally accomplished and a joy to read. I really, really do need to read more of Tim Pratt.

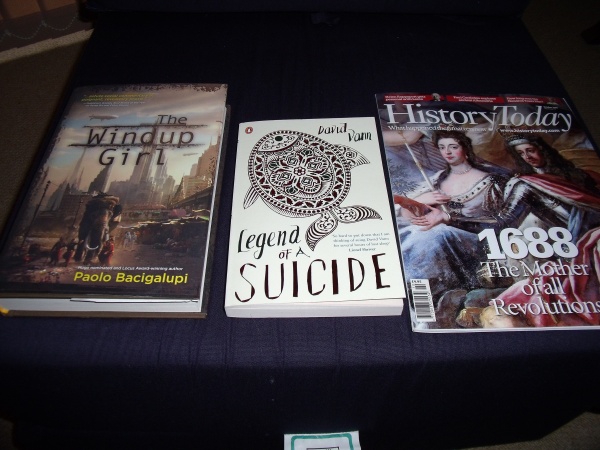

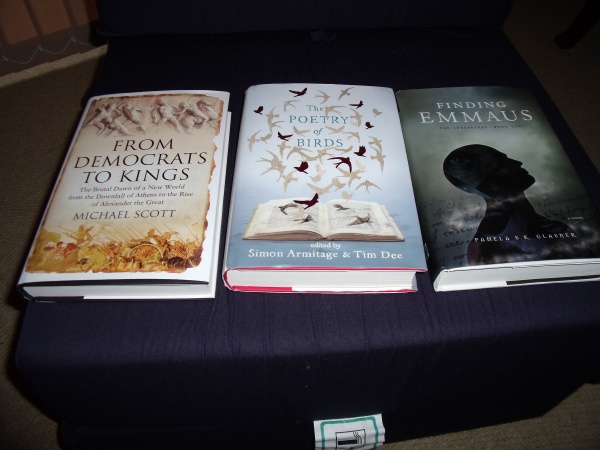

Late September books received

These actually are ‘books received’ (apart from one that I bought from the splendid Book Depository) — several competition prizes, a review copy, and the magazine was a complimentary copy.

Some interesting stuff there, I think.

Recent Comments