Acting on the prophecy of the witch queen Gullveig, King Athun takes twin boys from an Anglo-Saxon village during a raid. One, he names Vali and raises as his own; the other, Feileg, is kept by Gullveig to serve as her protector and sent to be schooled in the wolf-magic of the berserkers. Over the years, the twins become pawns in the complex game of magical subterfuge that is the eternal war between Odin and Loki. To say that Wolfsangel is a Viking fantasy with werewolves would technically be accurate but it would do a disservice to author Mark Barrowcliffe, whose debut fantasy (published under the name ‘MD Lachlan’) is a much richer book than that bald description suggests.

Acting on the prophecy of the witch queen Gullveig, King Athun takes twin boys from an Anglo-Saxon village during a raid. One, he names Vali and raises as his own; the other, Feileg, is kept by Gullveig to serve as her protector and sent to be schooled in the wolf-magic of the berserkers. Over the years, the twins become pawns in the complex game of magical subterfuge that is the eternal war between Odin and Loki. To say that Wolfsangel is a Viking fantasy with werewolves would technically be accurate but it would do a disservice to author Mark Barrowcliffe, whose debut fantasy (published under the name ‘MD Lachlan’) is a much richer book than that bald description suggests.

Wolfsangel pays its dues as a fantasy adventure story: the plot is suitably eventful, with twists and turns a-plenty, and Lachlan is a deft writer of action. But, while the violence in this novel may be brutal, it is not gratuitously so; the author brings home that violence plays a key part in the world of his story and he shows how harsh and restrictive it makes life for his characters. Vali is a prince who refuses to play the role expected of him by his society – he abhors fighting and his true love, Adisla, is a farm girl (who is far more resigned to the status quo than he). Perhaps his ultimate quest in Wolfsangel is to break free of those social strictures.

But Vali (and other characters) are bound in even deeper ways than they can imagine – and this is where magic comes in. Lachlan’s treatment of magic is interesting and distinctive, depicting a mysterious force that not even its ablest users understand fully (“a puzzle not a recipe” as one character puts it). Particularly striking is the way that this magic consumes and distorts those who wield and come into contact with it: the witch queen might have power enough to make her a goddess of sorts but the price she has paid is that her body will forever remain that of a child. Similarly, the magic of the berserks grants Feileg immense physical ability but it also twists his personality into something not quite human (“I am a wolf” he repeats, as though it were a mantra). The struggle to avert the destinies laid down by magic parallels Vali’s fight against society.

The whole world of Wolfsangel is suffused with the unknown. Gods are present in both divine and mortal aspects but aren’t necessarily aware of who they are. Magic floats through the narrative, with many seemingly unsure of where its reality stops and superstition begins. Even the geography, the very extent of the world, feels only half-known to most of the characters. It lends the book a real sense of strangeness, which runs alongside and rounds out the more conventional adventure story.

Wolfsangel is the first novel in a series that will move forwards through history; I’ll be interested to see how that works but, if the rest are a good as this one, it will be a series that needs reading.

This review first appeared in Vector 264, Autumn 2010

Elsewhere

Some other reviews of Wolfsangel: Paul Kincaid for Strange Horizons; Adam Roberts at Punkadiddle; Jonathan McCalmont at The Zone.

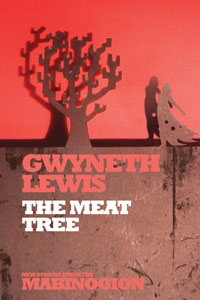

These are the latest two volumes in Seren Books’ series reworking the medieval Welsh tales of the Mabinogion. I don’t really know those myths, but, luckily for me, there’s a handy synopsis at the back of each book that helped me get up to speed. However, when I read the synopsis in Gwyneth Lewis’s The Meat Tree (based on the fourth branch of the Mabinogion, the story of

These are the latest two volumes in Seren Books’ series reworking the medieval Welsh tales of the Mabinogion. I don’t really know those myths, but, luckily for me, there’s a handy synopsis at the back of each book that helped me get up to speed. However, when I read the synopsis in Gwyneth Lewis’s The Meat Tree (based on the fourth branch of the Mabinogion, the story of  After that, Niall Griffiths’ (relatively) more conventional retelling of two dream stories in The Dreams of Max & Ronnie pales a little in comparison, perhaps. But, still,

After that, Niall Griffiths’ (relatively) more conventional retelling of two dream stories in The Dreams of Max & Ronnie pales a little in comparison, perhaps. But, still, The late 1990s saw the first case of what became known as Acquired Aposymbiotic Familiarism (AAF) – or, more bluntly, the Zoo Plague. Anyone who does something bad gains an animal (which is apparently an extension of their selves), a magical ability of some sort, and the threat of destruction by the “black cloud” of the Undertow. That “something bad” is deliberately vague, because nobody in the alternate present/several-months-hence of Lauren Beukes’ novel knows precisely what causes this condition; which of course means that people can place their own meaning on to it – but to become a “zoo” or “animalled” is certainly a social stigma.

The late 1990s saw the first case of what became known as Acquired Aposymbiotic Familiarism (AAF) – or, more bluntly, the Zoo Plague. Anyone who does something bad gains an animal (which is apparently an extension of their selves), a magical ability of some sort, and the threat of destruction by the “black cloud” of the Undertow. That “something bad” is deliberately vague, because nobody in the alternate present/several-months-hence of Lauren Beukes’ novel knows precisely what causes this condition; which of course means that people can place their own meaning on to it – but to become a “zoo” or “animalled” is certainly a social stigma.

Recent Comments