I’m splitting my review of the Goldsmiths shortlist into two parts. Here’s a look at three of the titles…

Eimear Bride, The Lesser Bohemians (2016)

Eimear Bride, The Lesser Bohemians (2016)

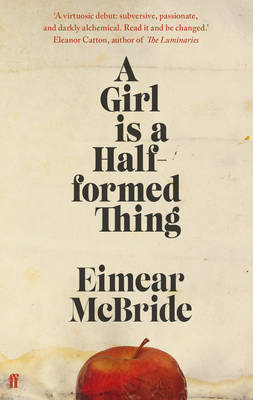

We’ll start with Eimear McBride, who of course won the vvery first Goldsmiths Prize in 2013, with A Girl is a Half-formed Thing. Her second novel is the story of Eilis, a young Irish woman who goes to study drama in London in 1994, and falls for an actor named Stephen, who is more than twice her age. Sounds conventional enough in the synopsis; but, as before with McBride, the novel is transformed by its language:

Goes on time so. Every day. Hours spent opening lanes of ways on which I might set forth. These are your oysters, boys and girls. Here are your worlds of pearls. I remember it as I sit in dust. Put on tights. Stretch on mats. Lean with hot drinks on stone steps where the throng pokes holes through shy.

A Girl is a half-formed Thing was written in a fragmented style which suggested that its narrator’s consciousness was not yet coherent – in the other words, the cohesion of voice (or lack of it) matched the cohesion of the character’s identity. The Lesser Bohemians could be seen as an extension of that technique: Eilis is further on in life than Girl’s protagonist, so her narrative voice is not quite as fragmented, but its rhythms are still noticeably jagged.

What really gives this novel its shape and contrast for me, however, is the section where Stephen tells Eilis his story – and his voice is rendered in a much more conventional literary style. This gives his life a semblance of order and control; but the events he describes don’t bear that out at all. So, McBride seems to suggest, a life is as coherent as the one living it allows; the tumult of the past will always be there, but – just maybe – it’s possible to bring oneself together eventually.

Anakana Schofield, Martin John (2015)

Conventionally, a novel is organised to create meaning for its reader. Even with a book like The Lesser Bohemians, where you have to work at it a bit, and where part of the meaning is encoded in the style, the general shape is recognisable and you can find your way around soon enough. Martin John is different: this is the form of the novel broken down and rebuilt to generate meaning for its protagonist; readers just have to derive what they can.

Martin John Gaffney lives in South London (his mam sent him away from Ireland). He works as a security guard, visits his Aunty Noanie every week. He loves the Eurovision Song Contest, but hates words that begin with the letter P. He is also a flasher. Martin John the novel is perhaps not so much his story (that would imply a narrative) as an account of his being.

Martin John’s existence is based around rituals and refrains, routines and circuits; these provide the structure that helps keep his life together (or, perhaps, keep his life at bay). The novel is built from looping, elliptical paragraphs:

With no day shift or night shift or circuits, time has become strange, neither protracted nor squat. Just strained. Strange. Estranged. Estuary ranged. There are days, inside the room, that because the windows are blacked out, he can’t tell you if it is day or night. He can’t tell if it’s night or day? He can’t even tell you how he wants to make this statement.

Martin John is a novel that lives with you, demands that you make space for it, uncomfortable as that inevitably will be. It places Anakana Schofield on my list of must-read authors.

Deborah Levy, Hot Milk (2016)

Deborah Levy, Hot Milk (2016)

As with reading Ishiguro, reading Deborah Levy has for me been a learning process. In both cases, when I read the author for the first time (Nocturnes and Swimming Home respectively), I wasn’t equipped to appreciate texts that had the appearance of stereotypical middle-class literary fiction, but distorted the form subtly, so that interpreting them literally didn’t work. I’m still finding my way.

In Hot Milk, 25-year-old Sofia Papastergiadis has travelled with her mother Rose to Almeria on the Spanish coast. Rose’s legs have been affected by a mysterious illness; it’s hoped that the Gómez Clinic in Almeria will provide a solution, but Sofia has surrendered her own life in order to come here – she’s even begun to copy Rose’s gait. It took me some time to get into the swing of the novel’s patterns of imagery and oblique characterisation. Even then, I can only see my understanding of it as provisional.

I came to the conclusion that Hot Milk was structured around metaphors of personal space: Sofia begins the novel having effectively subordinated her own identity to her mother’s; and the extent to which other characters encroach on her indicates how much Sofia is her own person. The scene that really seemed to unlock this is one where, hands bloodied from gutting a fish, Sofia rushes into the local diving school to free the owner’s dog, and ends up drinking the vermouth on his desk and leaving bloody handprints all over the walls. It seems strange if taken at face value, but made sense to me as a metaphor for Sofia exerting control over her surroundings.

I wouldn’t say that I unlocked Hot Milk entirely – I don’t have a sense of a complete metaphorical underpinning – but I was able to see Levy’s work in a new light. I now want to explore further, and hopefully come back to this book (and Swimming Home) one day, to see what else I can find there.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recent Comments