Matthias Politycki, Next World Novella (2009/11)

Matthias Politycki’s Next World Novella (translated from the German by Anthea Bell) is the latest title from Peirene Press, which would be enough on its own to interest me in reading the book, as I’ve enjoyed all their previous selections. Add to this that it’s a tale with shifting realities, and my interest only increases. Having read it now, though, it didn’t quite work for me, and I’m not sure I can put my finger on why.

Matthias Politycki’s Next World Novella (translated from the German by Anthea Bell) is the latest title from Peirene Press, which would be enough on its own to interest me in reading the book, as I’ve enjoyed all their previous selections. Add to this that it’s a tale with shifting realities, and my interest only increases. Having read it now, though, it didn’t quite work for me, and I’m not sure I can put my finger on why.

Academic Hinrich Schepp finds that his wife Doro has died at her desk, where she has apparently been editing the attempt at a novel that he abandoned years before. Reading the manuscript, Schepp discovers that Doro’s edits constitute a commentary on their marriage, and that his wife was far from as content as he’d assumed.

The beginning of Next World Novella is especially potent, as the reader is a fraction behind Schepp in realising that Doro has died, and anticipates the jolt which is to come. There’s also effective interplay between the gradual unfurling of Doro’s true feelings and Schepp’s inability/reluctance to perceive the truth (e.g. he refuses to acknowledge the extent to which his abandoned novel reflected his own life). Yet I finished the book feeling that I hadn’t quite grasped something about it, and I can’t put into words what that might be. Next World Novella is well worth a look, though.

Interview with Matthias Politycki (Worlds Without Borders)

Next World Novella elsewhere: Just William’s Luck; Cardigangirlverity; The Independent.

Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010)

A brilliant fusion of biography, social history, and history of science, that tells a fascinating story. Henrietta Lacks was a poor African American woman who died of cervical cancer in 1951; as with other cancer patients at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital, a sample of the cells from Henrietta’s tumour was taken, without her knowledge, for research purposes. Those cells were the origin of the HeLa cell line, the first human one to be propagated successfully in the lab (‘immortal’ because they can divide indefinitely in culture). Henrietta’s cells facilitated many medical advances, but it was twenty years before her family even learnt that a sample had been taken.

A brilliant fusion of biography, social history, and history of science, that tells a fascinating story. Henrietta Lacks was a poor African American woman who died of cervical cancer in 1951; as with other cancer patients at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital, a sample of the cells from Henrietta’s tumour was taken, without her knowledge, for research purposes. Those cells were the origin of the HeLa cell line, the first human one to be propagated successfully in the lab (‘immortal’ because they can divide indefinitely in culture). Henrietta’s cells facilitated many medical advances, but it was twenty years before her family even learnt that a sample had been taken.

Remarkable as this story is, it is Skloot’s treatment of it that makes The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. She moves back and forth between time periods and perspectives, weaving together details of Henrietta’s and her family’s lives; the wider social and scientific contexts; the ethical issues raised by Henrietta’s story; and Skloot’s own experiences meeting and interviewing the Lacks family. There’s great breadth to the material, and Skloot’s control of it is superb. What an engrossing read.

Rebecca Skloot’s website

Interview with Skloot (Wellcome Trust)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks elsewhere: SomeBeans; Savidge Reads; Take Me Away; Lovely Treez Reads.

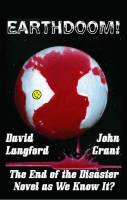

David Langford and John Grant, Earthdoom! (1987/2003)

A gloriously over-the-top spoof disaster novel featuring all manner of world-ending phenomena which appear on the scene in quick succession: a spacecraft on a collision course with Earth; an antimatter comet on a collision course with Earth; invading aliens; rabid lemmings; the Loch Ness Monster; a time-travelling Hitler who takes advantage of the handy cloning technology he finds on a Devon farm; sentient superglue… You get the idea.

A gloriously over-the-top spoof disaster novel featuring all manner of world-ending phenomena which appear on the scene in quick succession: a spacecraft on a collision course with Earth; an antimatter comet on a collision course with Earth; invading aliens; rabid lemmings; the Loch Ness Monster; a time-travelling Hitler who takes advantage of the handy cloning technology he finds on a Devon farm; sentient superglue… You get the idea.

Langford and Grant relentlessly send up the conventions of the disaster novel, with their cast of gung-ho male scientists and impossibly-attractive-yet-brilliant-except-when-the-guys-need-to-show-how-much-better-they-are female scientists; the plot contrivances which are eventually abandoned altogether when it suits; the characters’ helpful-for-the-reader recapping things they already know; and the prose. For example:

Jeb’s [the Devonian farmer] words rang hollow in his ears, not merely because in these grim days his accent was failing to convince even himself. Ambledyke Farmhouse was sealed against the horrors outside, its boarded-up windows blind as proofreaders’ eyyes. The inner dimness throbbed with a stench of ancient, decaying pizza. (p. 121)

Great stuff.

First published in English under the title The Satanic Mill, this German children’s classic (translated by Anthea Bell) has now been reissued under its original title as part of the

First published in English under the title The Satanic Mill, this German children’s classic (translated by Anthea Bell) has now been reissued under its original title as part of the  It starts simply enough: Emmi Rothner tries to cancel a magazine subscription, but mistypes the address and her email ends up in Leo Leike’s inbox. He notifies her of the mistake, and all is forgotten until, months later, Leo receives Emmi’s automated Christmas message and yet another email meant for the magazine. So begins an intimate email correspondence underpinned by something that may yet turn out to be love.

It starts simply enough: Emmi Rothner tries to cancel a magazine subscription, but mistypes the address and her email ends up in Leo Leike’s inbox. He notifies her of the mistake, and all is forgotten until, months later, Leo receives Emmi’s automated Christmas message and yet another email meant for the magazine. So begins an intimate email correspondence underpinned by something that may yet turn out to be love. My first choice for the

My first choice for the

Recent Comments