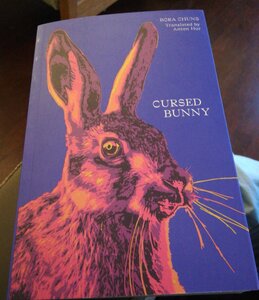

Oh, how I loved this. It’s not often that a story collection will grab my attention from the beginning and keep it throughout. But, for me, there isn’t a weak link among the ten stories in Cursed Bunny.

Bora Chung’s stories in this book are often strange, often creepy, always compelling. The title story concerns a family who make cursed objects. The grandfather tells his grandson how he broke the rules and cursed an object for personal use: a bunny-shaped lamp designed to wreak revenge on the company that destroyed his friend’s family business. Rabbits chew their way through the company’s paperwork, but they don’t stop there – and the tale takes some unexpected and horrific turns.

Some of Chung’s stories are built around powerful metaphors. In ‘The Embodiment’, a woman finds that her period won’t stop. She takes birth control pills for several months, to no avail – in fact, they make her pregnant. The doctors tell her that she must find someone to be the child’s father, or things will go badly for her. Societal pressures around motherhood and relationships are transformed into vivid narrative strokes that raise the protagonist’s predicament to a higher pitch of intensity.

There are entries in Cursed Bunny that read like fairy tales, though with Chung’s distinctive stamp. ‘Snare’ begins with a man coming across a trapped fox that bleeds liquid gold. He becomes rich from this, but eventually bleeds the fox to death. The man has the fox’s fur made into a scarf for his wife, who then falls pregnant. The man finds a way to obtain gold from his children, but at a terrible cost. This is a sharp parable of greed.

What really makes Cursed Bunny hang together for me is the voice. Anton Hur’s translation from Korean is beguiling, as it persuades the reader that all of this could happen. Bora Chung goes on to my list of must-read authors.

Published by Honford Star, a small press specialising in books from East Asia.

Read my other posts on the 2022 International Booker Prize here.

Recent Comments