I’m the featured blogger in this week’s Triple Choice Tuesday feature over on Kim’s blog, Reading Matters. This is a feature where Kim asks bloggers and other bookish folk to choose a favourite book, a book that changed their world, and a book that deserves a wider audience. I had great fun deciding on my three books, and writing about what they mean to me; I’d like to thank Kim for giving me the opportunity to take part.

Category: Non-Fiction

Book notes: Politycki, Skloot, Langford & Grant

Matthias Politycki, Next World Novella (2009/11)

Matthias Politycki’s Next World Novella (translated from the German by Anthea Bell) is the latest title from Peirene Press, which would be enough on its own to interest me in reading the book, as I’ve enjoyed all their previous selections. Add to this that it’s a tale with shifting realities, and my interest only increases. Having read it now, though, it didn’t quite work for me, and I’m not sure I can put my finger on why.

Matthias Politycki’s Next World Novella (translated from the German by Anthea Bell) is the latest title from Peirene Press, which would be enough on its own to interest me in reading the book, as I’ve enjoyed all their previous selections. Add to this that it’s a tale with shifting realities, and my interest only increases. Having read it now, though, it didn’t quite work for me, and I’m not sure I can put my finger on why.

Academic Hinrich Schepp finds that his wife Doro has died at her desk, where she has apparently been editing the attempt at a novel that he abandoned years before. Reading the manuscript, Schepp discovers that Doro’s edits constitute a commentary on their marriage, and that his wife was far from as content as he’d assumed.

The beginning of Next World Novella is especially potent, as the reader is a fraction behind Schepp in realising that Doro has died, and anticipates the jolt which is to come. There’s also effective interplay between the gradual unfurling of Doro’s true feelings and Schepp’s inability/reluctance to perceive the truth (e.g. he refuses to acknowledge the extent to which his abandoned novel reflected his own life). Yet I finished the book feeling that I hadn’t quite grasped something about it, and I can’t put into words what that might be. Next World Novella is well worth a look, though.

Interview with Matthias Politycki (Worlds Without Borders)

Next World Novella elsewhere: Just William’s Luck; Cardigangirlverity; The Independent.

Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (2010)

A brilliant fusion of biography, social history, and history of science, that tells a fascinating story. Henrietta Lacks was a poor African American woman who died of cervical cancer in 1951; as with other cancer patients at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital, a sample of the cells from Henrietta’s tumour was taken, without her knowledge, for research purposes. Those cells were the origin of the HeLa cell line, the first human one to be propagated successfully in the lab (‘immortal’ because they can divide indefinitely in culture). Henrietta’s cells facilitated many medical advances, but it was twenty years before her family even learnt that a sample had been taken.

A brilliant fusion of biography, social history, and history of science, that tells a fascinating story. Henrietta Lacks was a poor African American woman who died of cervical cancer in 1951; as with other cancer patients at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital, a sample of the cells from Henrietta’s tumour was taken, without her knowledge, for research purposes. Those cells were the origin of the HeLa cell line, the first human one to be propagated successfully in the lab (‘immortal’ because they can divide indefinitely in culture). Henrietta’s cells facilitated many medical advances, but it was twenty years before her family even learnt that a sample had been taken.

Remarkable as this story is, it is Skloot’s treatment of it that makes The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. She moves back and forth between time periods and perspectives, weaving together details of Henrietta’s and her family’s lives; the wider social and scientific contexts; the ethical issues raised by Henrietta’s story; and Skloot’s own experiences meeting and interviewing the Lacks family. There’s great breadth to the material, and Skloot’s control of it is superb. What an engrossing read.

Rebecca Skloot’s website

Interview with Skloot (Wellcome Trust)

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks elsewhere: SomeBeans; Savidge Reads; Take Me Away; Lovely Treez Reads.

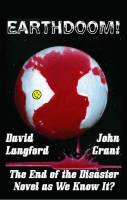

David Langford and John Grant, Earthdoom! (1987/2003)

A gloriously over-the-top spoof disaster novel featuring all manner of world-ending phenomena which appear on the scene in quick succession: a spacecraft on a collision course with Earth; an antimatter comet on a collision course with Earth; invading aliens; rabid lemmings; the Loch Ness Monster; a time-travelling Hitler who takes advantage of the handy cloning technology he finds on a Devon farm; sentient superglue… You get the idea.

A gloriously over-the-top spoof disaster novel featuring all manner of world-ending phenomena which appear on the scene in quick succession: a spacecraft on a collision course with Earth; an antimatter comet on a collision course with Earth; invading aliens; rabid lemmings; the Loch Ness Monster; a time-travelling Hitler who takes advantage of the handy cloning technology he finds on a Devon farm; sentient superglue… You get the idea.

Langford and Grant relentlessly send up the conventions of the disaster novel, with their cast of gung-ho male scientists and impossibly-attractive-yet-brilliant-except-when-the-guys-need-to-show-how-much-better-they-are female scientists; the plot contrivances which are eventually abandoned altogether when it suits; the characters’ helpful-for-the-reader recapping things they already know; and the prose. For example:

Jeb’s [the Devonian farmer] words rang hollow in his ears, not merely because in these grim days his accent was failing to convince even himself. Ambledyke Farmhouse was sealed against the horrors outside, its boarded-up windows blind as proofreaders’ eyyes. The inner dimness throbbed with a stench of ancient, decaying pizza. (p. 121)

Great stuff.

Simon Varwell, Up the Creek Without a Mullet (2010)

It was while travelling around eastern Europe with a friend that Simon Varwell developed a certain fascination with that [insert adjective of your choice here] hairstyle, the mullet. Back home in Inverness a year or so later, in 2002, Varwell discovered that there was a village in Albania named Mullet — and was taken with the notion of trying to visit everywhere in the world with the world mullet in its name. Up the Creek Without a Mullet chronicles the author’s travels up to 2005 (in Albania, Ireland, and mostly Australia), searching for mullets – places and haircuts alike.

It was while travelling around eastern Europe with a friend that Simon Varwell developed a certain fascination with that [insert adjective of your choice here] hairstyle, the mullet. Back home in Inverness a year or so later, in 2002, Varwell discovered that there was a village in Albania named Mullet — and was taken with the notion of trying to visit everywhere in the world with the world mullet in its name. Up the Creek Without a Mullet chronicles the author’s travels up to 2005 (in Albania, Ireland, and mostly Australia), searching for mullets – places and haircuts alike.

There’s a danger, I think, that this sort of travel writing can come to seem gimmicky, if the quirky reason behind the journey is given more weight than the journey itself. I’m pleased to say that doesn’t happen here, to the extent that I often felt as though the mullet-hunt was somewhat in the background; not forgotten about (on the contrary, it’s often on Varwell’s mind, to the point that he even wonders at times whether his ‘mission’ is all worth it), but it’s the cement that holds Varwell’s travels together — and, like cement, it’s not necessarily what you see first. Indeed, with Varwell’s often finding the ‘mullet’ places to be disappointingly ordinary, it’s his travels between that provide the greatest amount of interest.

Varwell himself proves a likeable companion for the journey through his book: he has a dry wit (at one point, he describes Sydney’s rail system as ‘reliable, good value, and regular, all novelties for a Scottish traveller’ [114]), writes engagingly about the places he visits, and makes Up the Creek Without a Mullet a very personal account. The idea behind Varwell’s journeys may be daft, but he’s well aware of that; and his genuine enthusiasm shines through, making this book a very satisfying read.

However, in case you were wondering: I’m keeping my hair short.

Further links

Simon Varwell’s website

Sandstone Press

Sydney Morning Herald article on Varwell’s travels (2005)

Mars in their Eyes by Colin Pillinger (2006)

One of those serendipitous finds I had in a charity book sale, this is the catalogue for an exhibition at the Cartoon Museum a few years ago. ‘Scientists are human too and enjoy a laugh as much as anybody, even if it is at their own expense,’ says Colin Pillinger in his introductory note, and I suppose he needed a sense of humour more than most.

I was surprised and impressed by the range of different kinds of Mars-themed cartoons on display here: there are political cartoons, cartoons about the search for alien life, cartoons about scientists, about missions to Mars (including, naturally, plenty concerning the ill-fated Beagle 2).Some of my favourites include Martians hurriedly scrawling ‘H.G. Wells Was Here’ on a rock before a satellite looks their way; a scientist taking great pains to stress the tentative nature of the evidence they’ve foudn that suggests there might have been life on Mars in the astronmically distant past — which has journalists screaming, ‘We’re not alone!’; and the Martian cup final being interrupted by the crash-landing space-probe that those hooligans from Earth sent up.

The cartoons are organised into chapters (some themed more loosely than others), each of which begins with a selection of facts about Mars and our exploration of the planet. Each cartoon also has its own piece of commentary by Pillinger; some of these are linked more tenuously than others, and the ‘flow’ between commentaries can feel disjointed at times.

But the cartoons make me wish I’d seen the exhibition; and Pillinger is a passionate and persuasive advocate of space exploration. His closing words ring true: ‘we should not discourage our children from asking difficult questions.’ And the cartoon accompanying this? Father-and-son aliens stand alone on a barren rocky world, looking up at the stars. The son asks, ‘Dad, do you think there’s life on other planets?’ ‘I dunno,’ comes the reply.

Recent Comments