Shawn the Book Maniac invited me back on his YouTube channel for another episode of Bite-sized Book Chats. This time we had a few words about Standing Heavy by GauZ’ (tr, Frank Wynne), the Ivoirian novel about security guards in Paris that I originally reviewed here on the blog. Check out our conversation below:

Category: French

Women in Translation Month: Completing Ágota Kristóf’s trilogy with The Proof and The Third Lie

Ágota Kristóf (1935-2011) was a Hungarian writer who lived in exile in Switzerland, and wrote in French, In 2014, I read The Notebook, her novel about twin boys driven to acts of cruelty in wartime and after. The brothers don’t allow themselves to express emotion, and the specifics of geography and time are diluted. I found the effect powerfully austere.

The Notebook is a complete experience in itself, but it’s also the first part of a trilogy. I’d always intended to read the rest, and now I have. It’s interesting to see how each volume casts the previous one in a different light.

The Notebook ended with the brothers separated: one crossed the border into a neighbouring country, the other stayed behind. This was, in its way, impossible to imagine, as the boys had narrated as one ‘we’ throughout. The Proof (tr. David Watson) picks the story up with the brother who returned home. Now, we learn his name: Lucas. This alone makes him seem more human and approachable, and we see Lucas trying to adjust to life alone, developing relationships with others and becoming an adult.

But it’s not as simple as that. Kristóf’s prose is as sparse as in The Notebook, creating a stark emotional distance. Lucas is still capable of cruelty, and there are times when we sense he’s being deeply affected by all he has been through – but he won’t let it show, and we can’t get close enough to him to really understand how he feels.

Geography and time are again flattened out, which heightens the sense of being trapped: years pass, yet everything feels essentially the same. But things are about to change when Lucas’s brother Claus finally returns, and suddenly what we’ve read is called into question.

The Third Lie (tr. Marc Romano) goes even further in breaking identities down. At the start, it is narrated by Claus, then at times appears to be narrated by Lucas, and at other times it’s not clear at all. Scenes from The Notebook are retold in a different form that challenge our fundamental assumptions: were there ever two brothers at all?

What I get most from Kristóf’s trilogy as a whole is the sense of being ultimately unable to reach the truth of what happened to its characters. There is great trauma in the background, yet it’s all words on paper in the end – and that, to me, is what gives the trilogy its power.

CB Editions publish a single-volume edition of Ágota Kristóf’s trilogy.

Naked Eye Publishing: Marseillaise My Way by Darina Al Joundi (tr. Helen Vassallo)

This dramatic monologue is the follow-up to Darina Al Joundi’s The Day Nina Simone Stopped Singing, which I wrote about earlier in the year. Once again, the translator is Helen Vassallo of the excellent Translating Women blog.

In Marseillaise My Way, Al Joundi’s protagonist Noun has left Beirut to make a new life for herself in France. As in the earlier play, a song runs through the piece, representing Noun’s situation. Before it was Nina Simone’s ‘Sinnerman’, which underlined Noun’s complex relationship with her father. Here it’s the Marseillaise, which Noun has to be able to sing as part of her French citizenship test.

Noun is uneasy about the words and often sings off-key. This represents a wider ambivalence that she feels towards France. She chose France because she thought it was the kind of secular country where she could have the freedoms she was denied in Lebanon. Yet she sees women and girls in France choosing to wear the veil and burka, and she can’t understand why. Experiences like this lead Noun to reflect on the Arab women who fought for freedom in the past.

The obstacles to Noun gaining citizenship keep piling up, as she has to navigate a maze of bureaucracy. But she remains determined to get there, to sing the Marseillaise her way. Her story is compelling.

Published by Naked Eye Publishing.

MacLehose Press: Standing Heavy by GauZ’ (tr. Frank Wynne)

GauZ’ is a writer from Côte d’Ivoire who spent time working as a security guard in Paris. That’s what his first novel revolves around: ‘standing heavy’ is slang for ” all the various professions that require the employee to remain standing in order to earn a pittance.” The prologue describes how immigrant Black men tend to fall into security guarding: it doesn’t need much experience, employers aren’t too bothered about your official status, and it’s a way to avoid being unemployed or on zero-hours.

Three main chapters chronicle the changing experiences of three Ivoirian security guards. In the 1960s and 70s, Ferdinand is optimistic even as French immigration policy changes. He feels he has a good job, and contrasts himself with the students in his residence, who (it seems to him) argue a lot but never actually do much.

By the 1990s, Ossiri and Kassoum are security guards in a Paris that takes their work for granted. “Send money back to the old country,” says a billboard, symbolising how much of an industry has built up around immigration. Ferdinand himself is now part of that industry, running his own business subletting security jobs. But everything will change in the aftermath of 9/11, when even the most menial security work becomes seen as too important to be left to Black men.

In between the main chapters are collections of snippets which represent the observations and thoughts of a security guard. For example, closing time at a store:

At the door, there is always someone swearing on her mother’s life that she will only need two minutes. The security guard is eyed with contempt when he refuses to grant these two-minute stays of execution. It is difficult to accept being snubbed by those one never notices. Here, everything is on sale, even self-esteem.

There’s a dry wit throughout Standing Heavy, which is really well conveyed in Frank Wynne’s translation. But there’s also a poignant side to the novel. To me, the chapters of fragments suggest a certain openness to the work of security guarding, which is not there in the closing image we have of Kassoum at work. By then, there are openings for Black security guards again, but it’s a much more regimented atmosphere. Standing Heavy presents a panoramic view of its characters’ world – it says so much in a relatively small space.

Links

- Publisher page on Standing Heavy

- More blog reviews by Tony and Stu

Click here to read my other posts on the 2023 International Booker Prize.

Naked Eye Publishing: The Day Nina Simone Stopped Singing by Darina Al Joundi

Time for something a little different today: a dramatic monologue. Darina Al Joundi is a Lebanese writer and actor now living in France. She first performed this one-woman play in 2007. She co-wrote a novel based on the play which has previously been translated into English, but this is the first English translation of the play itself. The translator is Helen Vassallo, who runs the excellent blog Translating Women (she’s written a post here on how she came to translate the play.

Al Joundi’s protagonist is Noun, whose father was a secular freedom fighter in a strict Muslim family. She interrupts his funeral, locking herself in the room with his body. She is there to carry out his wish to have Nina Simone’s ‘Sinnerman’ played at his funeral, rather than recitations from the Qu’ran. The monologue is Noun’s reflection on her life in Beirut, and on her father’s influence.

Noun’s father encouraged her to live as she wanted, and didn’t judge her. In turn, she looked up to him. For example, as a girl Noun tells her father that she wants to wear a bra. He warns her that she’ll find it painful and constricting, but she insists and he goes along with her wishes. Noun soon discovers that he was right.

There is humour running through Noun’s story, but she also experiences great violence – both personally and as part of the war escalating around her. In time, she has cause to question whether her father appreciated how free his daughter might really be in a society that didn’t share his values. Noun comes across as a vivid, complex character in this thought-provoking piece of work.

Published by Naked Eye Publishing.

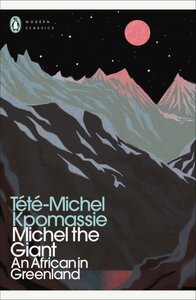

Michel the Giant: An African in Greenland

Originally published in French in 1977, this is a travelogue by Togolese writer Tété-Michel Kpomassie (translated by James Kirkup). As a teenager in the 1950s, he is (reluctantly) about to be initiated into a snake cult when he reads a book about Greenland. This place is beyond anything he has experienced or can imagine, but there will be no snakes – and, he reads, “the child is king, free from all traditional and family restraint”. This is enough to make the young Kpomassie resolve to travel to Greenland, even though it means running away from home.

Kpomassie’s journey to Greenland is an epic tale in itself. It takes six years for him to earn enough money to leave Africa, followed by a spell working in Paris before he finally reaches his destination. He stands out, not just for his skin colour but also his height (hence he’s nicknamed Michel the Giant). This will be a two-way meeting of cultures: “I had started on a voyage of discovery, only to find that it was I who was being discovered.”

Kpomassie’s book is a fascinating account of his travels. There are telling details, such as the cinema that stops foreign films every ten minutes to explain the action to the Inuit audience, because only Danish subtitles are available. These episodes are mixed with Kpomassie’s broader reflections on the people he encounters. His openness and willingness to meet Greenland on its own terms are what make Michel the Giant so engaging for me.

Published by Penguin Modern Classics.

MacLehose Press: The Sky Above the Roof by Nathacha Appanah (tr. Geoffrey Strachan)

I’m intrigued by the way that the brevity of a short novel can bring a distinctive feel to familiar subject matter. One of the Boys by Daniel Magariel springs to mind here, the way it puts a toxic family relationship into extreme close-up by removing all but the most essential detail.

Another example is The Sky Above the Roof, the latest novel to appear in English by Mauritian-French author Nathacha Appanah. It revolves around three characters who are all, in some way, ill at ease in the world. We begin with young Wolf in the back of a police van. He drove on the wrong side of the road, there was a crash, and now here we are. To an outside observer, Wolf may just seem a boy who doesn’t pay attention. In fact, though his mind mixes up times and memories of events, his mechanical instinct is something else. His mother thinks of him like this:

…a boy who does not have a licence and cannot catch a bus on his own, suffers from anxiety attacks and can go for days without speaking. One who has magic fingers and can repair little things when they break down (hairdryer, telephone, power drill), his gaze acting like a scanner and detecting where the fault lies. He who can run round and round the house for two hours without stopping, is afraid of the hollow in the garden and, now, does not want to see her.

At the time of the crash, Wolf was driving to visit his sister Paloma, who walked out years ago. Paloma is someone who hides on the sidelines of life. Then there’s the siblings’ mother, who was named Eliette as a girl, and hated the way her parents made her dress up and sing – which is to say nothing of where that led. She made a life for herself as an adult, changing her appearance and calling herself Phoenix. She also made sure that she wouldn’t constrict her children in the way her parents did with her – but, as we see, not everything turns out as intended.

The Sky Above the Roof has 130 pages and encompasses this family’s immediate history, as well as Wolf’s brief (though still harrowing) stay in the remand centre. It seems to me that the novel loses some nuance of cause and effect through its brevity: sometimes it feels as though upbringing is the be-all and end-all. But its shortness also brings Appanah’s book intensity, making it a string of set-pieces with that swirling prose in Geoffrey Strachan’s fine translation.

Published by MacLehose Press.

My favourite books read in 2021

Here we are again, approaching the end of another year. As usual, I’ve picked out my twelve favourite books that I read in 2021, regardless of when they were first published. I always find that doing this provides me with an interesting snapshot of my reading year as a whole. This year’s snapshot has given me cause to reflect – but more on that in another post. For now, here are my reading highlights of 2021:

12. Angélique Villeneuve, Winter Flowers (2014)

Translated from French by Adriana Hunter (2021)

A novel set in the aftermath of World War One, in which a woman tries to rebuild her relationship with her disfigured husband, while the community around comes to terms with its own traumas. Winter Flowers is one of those books that cuts through preconceived notions about its subject matter to capture raw feeling.

11. Judith Bryan, Bernard and the Cloth Monkey (1998)

If it hadn’t been for the ‘Black Britain: Writing Back‘ series curated by Bernardine Evaristo, I might never have come across Bernard and the Cloth Monkey. I’m so glad I did. This tale of a young woman returning to her family home constantly shifts in register, creating a kaleidoscope of emotion in a seemingly ordinary setting.

10. Adam Mars-Jones, Batlava Lake (2021)

I like stories that are shaped by a strong narrative voice, and that’s very much the case with Batlava Lake. Mars-Jones introduces us to Barry, a matey, chatty engineer who’s really not equipped to convey the brutality of war in Kosovo. But that very inadequacy is what makes the book work so well.

9. Andrew Komarnyckyj, Ezra Slef, the Next Nobel Laureate in Literature (2021)

Of all the books I read in 2021, I think this was probably the most fun. It’s a spoof literary biography whose purported author talks more about himself than his subject, and deals with a Twitter troll by (inadvertently) making a deal with the Devil. Just thinking back to reading Ezra Slef makes me smile.

8. Rebecca Watson, little scratch (2021)

little scratch was the least conventionally written novel that I read all year, with its words scattered in different patterns across the page. Those words are the thoughts of a young woman going about her day while something plays on her mind. It’s a technique that really brought me close to the narrator and the tension that grows throughout the book.

7. Ivana Dobrakovová, Bellevue (2009)

Translated from Slovak by Julia and Peter Sherwood (2019)

This book was probably my biggest surprise of the reading year, in that I wasn’t prepared for the way it turns, so subtly and effectively. Its protagonist takes a summer job working with disabled people, but struggles to cope. Her mental health is affected, which we see entirely through changes in the shape of her narration – which is what makes the effect so powerful.

6. Natasha Brown, Assembly (2021)

More shapeshifting prose here, but in this case the protagonist is finding her voice. A Black British woman working in the banking industry reflects on her situation, and asks herself how she really wants to be. The prose is constantly changing to match her thoughts as she assembles the pieces of her life, building to a crescendo for narrator and reader alike.

5. Isabel Waidner, Sterling Karat Gold (2021)

A worthy winner of the Goldsmiths Prize, this novel strikes me as a carnival – in the sense of both an entertainment and a festival challenging social structures. Sterling and their friends face a nightmarish authoritarian world that works against them in ways they don’t understand. There are matadors, showtrials, time-travelling spaceships – and hope to be found in pushing back.

4. Federico Falco, A Perfect Cemetery (2016)

Translated from Spanish by Jennifer Croft (2021)

I love story collections that work as a whole, and this one certainly does. Falco’s protagonists are all facing pivotal moments of change in their lives, and his stories are suitably dynamic. There’s a great sense of place and character about these tales, and each one opens out memorably as it ends.

3. Claudia Piñeiro, Elena Knows (2007)

Translated from Spanish by Frances Riddle (2021)

Elena has Parkinsons, and this novel is structured around the ebb and flow of her energy levels. She’s forced to confront the limits of her knowledge about her daughter, which reflects the limits of what she can do during the day. With so many of the books on my list, the language brought me right into the protagonist’s world – perhaps none more so than Elena Knows.

2. Jon McGregor, Lean Fall Stand (2021)

I was intrigued at the prospect of a Jon McGregor novel set partly in the Antarctic. In the end, I experienced Lean Fall Stand as viscerally as any of his others. A polar guide tries to rebuild his life and self after a stroke. McGregor explores how language breaks down and re-forms around this event, in a dizzying rush of a novel.

1. Paul Griffiths, The Tomb Guardians (2021)

The single most powerful reading experience I had in 2021 was this slim novel interweaving conversations between the guardians of Christ’s tomb and a present-day lecturer examining 16th-century depictions of them. The book hovers on the knife-edge of uncertainty, and rivals Convenience Store Woman for the sudden power of its ending. This is why I’m reading fiction in the first place.

***

There we go. I hope you’ve found some books in 2021 that you enjoyed as much as I did these. If you’d like to see my selections from previous years, you can find them here: 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, and 2009. As ever, thank you for reading, and I’ll see you next year – you can also catch me on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

Peirene Press: Winter Flowers by Angélique Villeneuve (tr. Adriana Hunter)

This latest title from Peirene Press takes us to Paris in 1918, where we meet Jeanne, who makes paper flowers for a living. Her husband Toussaint has been recovering from facial injuries sustained in the war. He told her not to visit him in hospital, and she has feared the thought of what’s happened to him.

Now, Toussaint has returned home, face covered, unable to speak. Not only is he a stranger to Jeanne, she struggles to see him as a person at first:

She doesn’t think, He’s here, she thinks, It’s here. This unknown thing that’s coming home to her. That she’s dreaded, and longed for. It’s here. It’s going to come in, it’s going to make its life with her, and with Léo [their daughter] too, it will come here, into this room that the two of them have shared so little since they left Belleville

Jeanne could be talking about Toussaint’s disfigurement in the abstract here, as much as Toussaint the person. Winter Flowers reminds me of David Diop’s At Night All Blood Is Black, in that both are First World War novels which strongly evoke sensation and feeling. Hunter’s translation is so vivid, as Villeneuve’s novel explores not just Jeanne and Toussaint working out how to relate again, but also the different traumas of the community around them. This is the first of Villeneuve’s novels to appear in English translation; I hope there will be more.

#2021InternationalBooker: The War of the Poor by Éric Vuillard

This slim volume (under 100 pages) introduced me to an unfamiliar name from history: Thomas Müntzer, a preacher who became a leading figure in the German Peasants’ War of 1525. He opposed both the Roman Catholic Church and Martin Luther, and he went from questioning the prevailing theology to encouraging more general revolt against the ruling authorities.

There’s a real sense in Vuillard’s prose of dynamic and open-ended societal change. For example, I loved this passage describing the effects of the printing press:

Fifty years earlier, a molten substance had flowed from Mainz over the rest of Europe, flowed between the hills of every town, between the letters of every name, in the gutters, between every twist and turn of thought; and every letter, every fragment of an idea, every punctuation mark had found itself cast in a bit of metal.

Translation from french by mark polizzotti

Vuillard places Müntzer in a line of popular rebels and preachers, including Wat Tyler and Jan Hus. The restlessness of rebellion is reflected in the way Vuillard writes and structures his book (and, of course, Polizzotti’s translation). Ultimately, The War of the Poor may be a little too slight to really shine for me, but it certainly has powerful moments.

Published by Picador.

Read my other posts on the 2021 International Booker Prize here.

Recent Comments