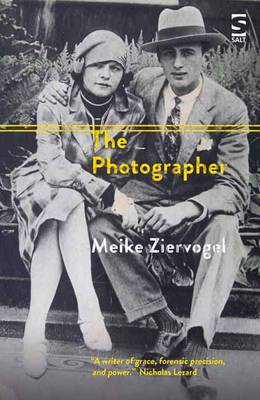

You might know Meike Ziervogel best as the publisher of Peirene Press; but she’s also built a career as a novelist over the last few years. The Photographer is her fourth novel (published, like the others, by Salt), and draws upon the history of the 11 million Germans who fled west in 1945 to escape the fighting. Like Han Kang’s Human Acts (albeit in a rather different way), Ziervogel’s book examines a large human event at an intensely individual scale.

In a small Pomeranian town, a young girl named Trude dreams of being whisked away by her prince. In 1933, shortly after turning eighteen, she finds him: a photographer named Albert. His work allows the couple to travel Europe; later they have a son, Peter. However, Trude’s mother Agatha never takes to Albert: he’s “a boy from the gutter”, not fit for her daughter. Discovering from Peter that Albert listens to enemy radio is all the pretext Agatha needs to report him to the authorities and get him sent to the front. In 1945, the family is forced to leave for Berlin before Albert has returned. The rest of Ziervogel’s novel chronicles how this broken family heals itself.

Appropriately enough given its title, The Photographer revolves around themes of image and appearance, which are often tied to social status. So, for example, we begin with Trude’s dreams of a romantic life – which, for a while, she gets. But, when the family flees to Berlin, those dreams come crashing down around her:

She hasn’t even put on any lipstick and looks like a common woman with a tear-stained face whose husband has just been taken away, has just died. There are thousands and thousands of these women. She feels ashamed to be one of them now.

All of a sudden, Trude feels that her individual, exceptional story has collapsed into something generic: the tale of any other refugee wife. To an extent, she’s right: in the grand sweep of history, she will become part of a statistic, one of those 11 million people. What Trude overlooks, though, is that each of the refugees has their own life, as rich to them as hers is to herself.

In 1947, the family is reunited after Albert has been released from Russian captivity. Here, there is a key lack of images: Albert and Peter can’t remember what the other used to look like, and therefore can’t recognise each other in the present. They have to get to know each other from first principles in order to bridge the gap of the years

Albert’s sense of displacement extends to how he has come to think of photography:

While before the war the camera was his extended eye, which he used to capture his view of the world, it was now what protected him, behind which he hid, which kept him, the real Albert, at a distance. Far, far away from everything that was happening around him.

Where Albert once faced the world with confidence, now photography is just about his only point of stability. No surprise, perhaps, that he attempts to reach Peter by trying to get him interested in photography, although the boy would rather spend his time boxing. Ultimately, it seems, Albert and Peter need to learn to see the world through each other’s eyes.

The Photographer has that wonderful combination of being dense with reading, yet with an openness to the writing. The novel is structured like a photo album: whole lives are narrated, but intermittently. Some events are told in detail; others have to be inferred by the reader; still others are so private that they don’t appear on the page. This is a novel of history as something lived through and looked back on, vivid incidents scattered among the threads of life.

Other reviews

Read other reviews of The Photographer by Mika Provata-Carlone at Bookanista, and Jackie Law at Bookmunch.

Book details

The Photographer (2017) by Meike Ziervogel, Salt Publishing, 171 pages, paperback (review copy).

Like this:

Like Loading...

Patrick Ness

Patrick Ness

Recent Comments