A few years ago, I enjoyed Michael Stewart’s debut novel, King Crow – so I was really pleased to discover that he had a new book out. Café Assassin is quite different in subject from its predecessor, but it has the same tension, rooted in a strong first-person voice that feels as though it could go anywhere.

A few years ago, I enjoyed Michael Stewart’s debut novel, King Crow – so I was really pleased to discover that he had a new book out. Café Assassin is quite different in subject from its predecessor, but it has the same tension, rooted in a strong first-person voice that feels as though it could go anywhere.

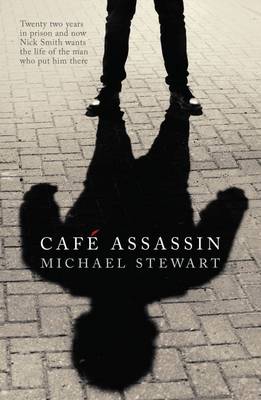

The owner of that voice is Nick Smith, newly released from prison twenty-two years after being wrongly convicted of murder. His words are addressed to Andrew Honour, a childhood friend on whom Nick now seeks revenge. Nick looks at Andrew’s life – a successful job as a QC, happily married to his old girlfriend Liv, on whom Nick always had a crush – and wants what he sees. Over the course of the novel, Nick gets back on his feet, and gradually inveigles his way into Andrew’s and Liv’s lives – but to what end?

I found Café Assassin to have an enormous narrative pull, which comes from the ambivalent attitude we develop towards Nick: we know he has seriously been wronged, but we also learn what a violent individual he can be; we want Nick to have some sort of resolution, but not necessarily the kind of revenge it appears he’s working towards. Beyond the plot, there’s a mutable quality to Stewart’s prose, and the sense of identity Nick creates in his account. Nick has to remind himself that it’s not 1989 but 2011, and there a constant sense of dislocation as the gap of years is opened and bridged and opened again. Then there are the interstitial chapters in second-person, which describe Nick’s life in prison; these aren’t a straightforward contrast with the first-person text, but intersect with it at right-angles, adding a further layer of complexity. If we never quite know where Café Assassin will end up, perhaps it’s because we never quite have the measure of its protagonist – and the sense is that perhaps he doesn’t even have the full measure of himself.

Café Assassin is published by Bluemoose Books.

Several hours before Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending was named as the winner of this year’s Man Booker Prize, The Guardian announced the result of its third annual ‘Not the Booker Prize’, voted for by readers of its books blog. The winner was Michael Stewart’s debut, published by the Hebden Bridge-based

Several hours before Julian Barnes’s The Sense of an Ending was named as the winner of this year’s Man Booker Prize, The Guardian announced the result of its third annual ‘Not the Booker Prize’, voted for by readers of its books blog. The winner was Michael Stewart’s debut, published by the Hebden Bridge-based

Recent Comments