I’m late in covering this, as the Man Booker International winner was announced last Wednesday. Although the official and shadow shortlists had only two books in common, the judges came to the same conclusion as the shadow panel: Flights by Olga Tokarczuk (tr. Jennifer Croft) took the Prize. Congratulations to both author and translator, and of course to publisher Fitzcarraldo Editions.

Author: David Hebblethwaite

#MBI2018 Shadow Panel Winner

It’s been ten weeks since the Man Booker International Prize longlist was announced, and in that time the Shadow Panel has been working away in the background, reading frantically while discussing the merits and flaws of the selected titles. From the thirteen books we were given by the official judges, we chose a shortlist of six (only two of which made the official cut!), and off we set again, to reread as much as possible in the time we had. Then we discussed the books a little more before voting for our favourites, culminating in the choice of our favourite work of translated fiction from the previous year’s crop. And who might that be?

THE WINNER OF THE 2018 SHADOW MAN BOOKER INTERNATIONAL PRIZE IS:

OLGA TOKARCZUK’S FLIGHTS

(FITZCARRALDO EDITIONS, TRANSLATED BY JENNIFER CROFT)

Congratulations to all involved! While not a unanimous decision, Flights easily won the majority of votes from our judges. In fact, in the seven years we’ve been shadowing the prizes (IFFP, then MBIP), this was the clearest winner by far, showing how impressed we were by Tokarczuk’s integration of seemingly disparate pieces into a mesmerising whole. Thanks must also go to Croft for her excellent work on the book – as always, it’s only with the help of the translator that we’re able to read this book at all…

A special mention should also go to Fitzcarraldo Editions. This is their second consecutive MBIP Shadow Prize (we selected Mathias Énard’s Compass as our winner for 2017), and having also come close with Énard’s Zone in 2015 (which wasn’t even selected for the official IFFP list that year!), they have proved to be one of the UK’s rising stars of fiction (and non-fiction) in translation. We look forward to seeing whether they can continue to provide titles for the longlist in future years.

*****

And that’s it for 2018…

Firstly, thank you to the rest of our Shadow Panel. While Tony, Bellezza and Lori were around to help once more, it was a new-look team this year, with Paul, Vivek, Naomi, Oisin and Frances joining the crew. It’s been fascinating to compare our opinions about the books, even (or especially!) when we disagreed about them. Here’s hoping that we can do it all again next year!

Secondly, a shout-out to all the readers and commenters out there. It’s heartening to have people appreciate our endeavours, and when people say that they’re following the prize vicariously through our reviews and comments, even if they don’t have time to read all the books themselves, it makes us feel as if the whole process is worth it.

Finally, thank you to the official judges for taking the time to read an awful lot of books in order to select the cream of the crop (although occasionally there’s a suspicion that the milk has gone rather sour…). We hope that their final choice (to be announced about twenty-four hours after ours) is a worthy winner to round off this year’s prize. Who will it be? Come back soon to find out…

Adapted from an original post on Tony’s Reading List.

Zero Hours – Neil Campbell

Zero Hours is Neil Campbell’s second novel, the sequel to 2016’s Sky Hooks (which I haven’t read, though the new book mostly stands alone). As its title suggests, this is a novel about work:

Try doing some of this zero hours shit. If you’re off sick then drag your arse in because you won’t be getting sick pay, you’ve got no rights whatsoever. Day after day you phone in asking for work. Day after day you sign in at the desk, just another face from the agency. On the phone, they used to call you for work. Now you have to call them. Time after time it’s engaged.

Campbell’s narrator is a young working-class man from Manchester. Throughout the novel he works a number of zero hours jobs, first at a mail-sorting depot, later at a number of libraries. There is nearly always something to dishearten our man, be it his duties, colleagues, managers, or just the constant uncertainty that comes with this kind of employment. Besides work, the narrator has a number of unsuccessful attempts at relationships, and sees the face of his city change, losing its character to gentrification. There’s a stop-start feel to reading the novel itself: as with zero hours work, the present moment is all, and even the immediate future uncertain.

Alongside his ‘day job’, the protagonist is a writer, active in the local literary scene and with a number of books published. This comes across as the glue holding the man’s life together, a source of continuity in contrast to pretty much everything else happening in his world. Sometimes reading Zero Hours feels like eavesdropping; at other times, it’s like being confided in. It makes one hope that, by novel’s end, there will be some light on the horizon.

Book details

Zero Hours (2018) by Neil Campbell, Salt Publishing, 138 pages, paperback (source: review copy).

Read my review of Neil Campbell’s chapbook ‘Jackdaws’ (Nightjar Press) here.

Soviet Milk – Nora Ikstena

Today I’m looking at a book from Latvia, the first title in Peirene‘s ‘Home in Exile’ series for 2018. Two unnamed first-person narrators alternate: a mother and daughter. The mother is born in Riga in 1944 and becomes a talented doctor, offered a position to study in Leningrad. She gives birth to a daughter in 1969, but struggles with the prospect of being a mother: she disappears for five days immediately following the birth, and remains distant from her daughter, who is brought up mostly by her grandmother and step-grandfather.

All this changes, however, at the turn of 1977/8, when the mother has a run-in with the Soviet bureaucracy which ends with her being sent to run an ambulatory station in the Latvian countryside. She takes her daughter to live with her, hoping to grow closer to her – but depression continues to overshadow the mother’s life. There’s a stark quality to Nora Ikstena’s prose (in Margita Gailitis’ translation) that really heightens the intensity of her subject matter.

Milk is a recurring motif throughout the book: for example, the mother fears that she will poison her daughter if she breastfeeds, and the girl grows to be lactose intolerant. This works effectively as a metaphor for the troubled mother-daughter relationship at the novel’s heart, but also as a metaphor for the relationship between Latvia and the Soviet Union. The mother longs for Latvia to gain its independence, while the daughter starts to learn about Latvian culture at a clandestine after-school group. As the novel approaches its end in 1989, change is on the horizon, but the way for the two protagonists to reach there remains uncertain.

Soviet Milk is a fine example of a human story that refracts to illuminate a wider picture, and works well at both the small and large scales. I’ll be looking out for more of Ikstena’s work in translation in the future.

Book details

Soviet Milk (2015) by Nora Ikstena, tr. Margita Gailitis (2018), Peirene Press, 192 pages, paperback (source: review copy).

Man Booker International Prize 2018: the shadow panel’s shortlist

The scores are in, and we have our shadow shortlist:

- The Impostor by Javier Cercas, tr. Frank Wynne (Spain, MacLehose Press).

- The White Book by Han Kang, tr. Deborah Smith (South Korea, Portobello Books).

- Die, My Love by Ariana Harwicz, tr. Sarah Moses and Carolina Orloff (Argentina, Charco Press).

- The Flying Mountain by Christoph Ransmayr, tr. Simon Pare (Austria, Seagull Books).

- Flights by Olga Tokarczuk, tr. Jennifer Croft (Poland, Fitzcarraldo Editions).

- The Stolen Bicycle by Wu Ming-Yi, tr. Darryl Sterk (Taiwan, Text Publishing).

Go, Went, Gone and Frankenstein in Baghdad receive honourable mentions from the shadow panel.

We’ve ended up with quite a different shortlist from the official one (only two titles in common) – but of course that’s all part of the fun!

The winner of this year’s MBIP will be announced on 22 May, with the shadow winner revealed shortly before.

Man Booker International Prize 2018: the shortlist

The judges of the 2018 Man Booker International Prize announced their shortlist on Thursday:

- Vernon Subutex 1 by Virginie Despentes, tr. Frank Wynne (France, MacLehose Press).

- The White Book by Han Kang, tr. Deborah Smith (South Korea, Portobello Books).

- The World Goes On by László Kraznahorhai, tr. John Bakti, Ottilie Mulzet and George Szirtes (Hungary, Tuskar Rock Press).

- Like a Falling Shadow by Antonio Muñoz Molina, tr. Camilo A. Ramirez (Spain, Tuskar Rock Press).

- Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi, tr. Jonathan Wright (Iraq, Oneworld).

- Flights by Olga Tokarczuk, tr. Jennifer Croft (Poland, Fitzcarraldo Editions).

I ended up prioritising reading over reviewing this year, so I haven’t been talking much about the longlist on here. Suffice it to say that my two favourite books were Frankenstein in Baghdad and The White Book (which I still hope to review), so I’m pleased to see them both on the shortlist.

We’ll be announcing the shadow panel’s shortlist this coming Thursday. Watch this space…

The Dinner Guest – Gabriela Ybarra (#MBI2018)

The opening of Gabriela Ybarra’s debut novel (longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker International Prize) explains its title:

The story goes that in my family there’s an extra dinner guest at every meal. He’s invisible, but always there. He has a plate, glass, knife and fork. Every so often he appears, casts his shadow over the table and erases one of those present.

The first to vanish was my grandfather.

[translation by Natasha Wimmer]

The novel narrates and juxtaposes two deaths in the author’s family; a prefatory note suggests that this is Ybarra’s way of trying to come to terms with what happened.

The first part of The Dinner Guest focuses on Ybarra’s grandfather Javier, a Basque politician who was kidnapped by separatists in 1977 (six years before the author was born), then killed after a month of unsuccessful negotiations. The second section mostly concerns the death from cancer of Ybarra’s mother. There lies the contrast at the novel’s heart: on the one hand, public events which are told at a certain remove; on the other, a more private, intimate loss.

There are some poignant moments as Ybarra depicts her mother’s decline, but the novel is also striking when she brings the different strands together. For example, Ybarra searches the internet for images of the man who sent her father a package bomb in 2002, and finds herself experiencing a particular that she can’t quite pin down:

Looking at pictures of him, I feel the same way I do when I look at images of cancer cells. I don’t think about the threat, but about the story conjured up. The images of the tumours look like galaxies, and when I look at them, I tell myself stories about space.

It’s that impulse, to make stories out of what could be seen as threatening, which drives the form of this novel. The intersection of those different stories is intriguing.

This post is part of a series on the 2018 Man Booker International Prize; click here to read the rest.

Book details

The Dinner Guest (2015) by Gabriela Ybarra, tr. Natasha Wimmer (2018), Harvill Secker, 160 pages, paperback (source: review copy).

Frankenstein in Baghdad – Ahmed Saadawi (#MBI2018)

Frankenstein in Baghdad is Ahmed Saadawi’s third novel (although, as far as I can tell, the first to be translated into English). It won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2014, making Saadawi the first Iraqi writer to win the award. If I’m honest, though, my attention was caught by the title alone.

The setting is US-occupied Baghdad. We are quickly introduced to a number of memorable characters, including Elishva, an old woman believed to have special powers, who still longs for her son Daniel to return from the Iran-Iraq war; Hadi, an old junk-seller and teller of tall tales; and Mahmoud, an ambitious magazine journalist. In the first few chapters especially, the view of events overlaps as we go from character to character, so already we get a sense of shifting, unstable reality.

This is a place where danger and violence can erupt without warning:

When he was twenty yards past the gate, Hadi saw the garbage truck race past him toward the gate, almost knocking him over. A few moments later it exploded. Hadi,together with his sack and his dinner, was lifted off the ground. With the dust and dirt and blast of the explosion, he sailed through the air, turned a somersault, and landed hard on the asphalt.

Hadi has been collecting body parts and stitching them together, hoping that the government will give the pieces a proper burial if they’re part of a complete corpse. The corpse, however, has other ideas. The soul of a hotel guard killed by that exploding garbage truck finds a resting place in Hadi’s creation, and it only takes an inadvertent wish from Elishva to animate the body… and soon she thinks Daniel has returned.

But then the corpse – soon to be dubbed “the Whatsitsname” – disappears, and gains a gruesome purpose. He is driven to kill those responsible for the deaths of his individual parts. But, whenever the Whatsitsname kills such a person, his corresponding body part disintegrates – and so needs to be replaced, leading to another urge to kill, and so on, and so on. The Whatsitsname becomes a walking cycle of killing for its own sake. This becomes a powerful metaphor for life in the besieged city. It grows even more grimly absurd when the Whatsitsname attracts his own acolytes willing to assist his cause, so ending up at the centre of a cult-of-sorts.

But… what if it’s all not real? Saadawi builds enough trapdoors into his novel that the whole business of the Whatsitsname could be false. The Whatsitsname purportedly tells his story on a digital voice recorder provided by Mahmoud, via Hadi – at two or more removes, in other words, with one of those being a notorious liar. Furthermore, the whole book is presented as a text written by an unidentified author and found by a shady government department. The effect of all this is not so much to undermine the Whatsitsname as to reinforce the notion that he’s not needed – all the absurdity, the random killing, can and does go on anyway.

Jonathan Wright’s translation is measured in tone, making the supernatural grounded and everyday horrors all the more shocking. I thoroughly enjoyed reading Frankenstein in Baghdad, and it will be my benchmark as I go through the Man Booker International longlist.

This post is part of a series on the 2018 Man Booker International Prize; click here to read the rest.

Book details

Frankenstein in Baghdad (2013) by Ahmed Saadawi, tr. Jonathan Wright (2018), Oneworld, 272 pages, paperback (proof copy provided for review).

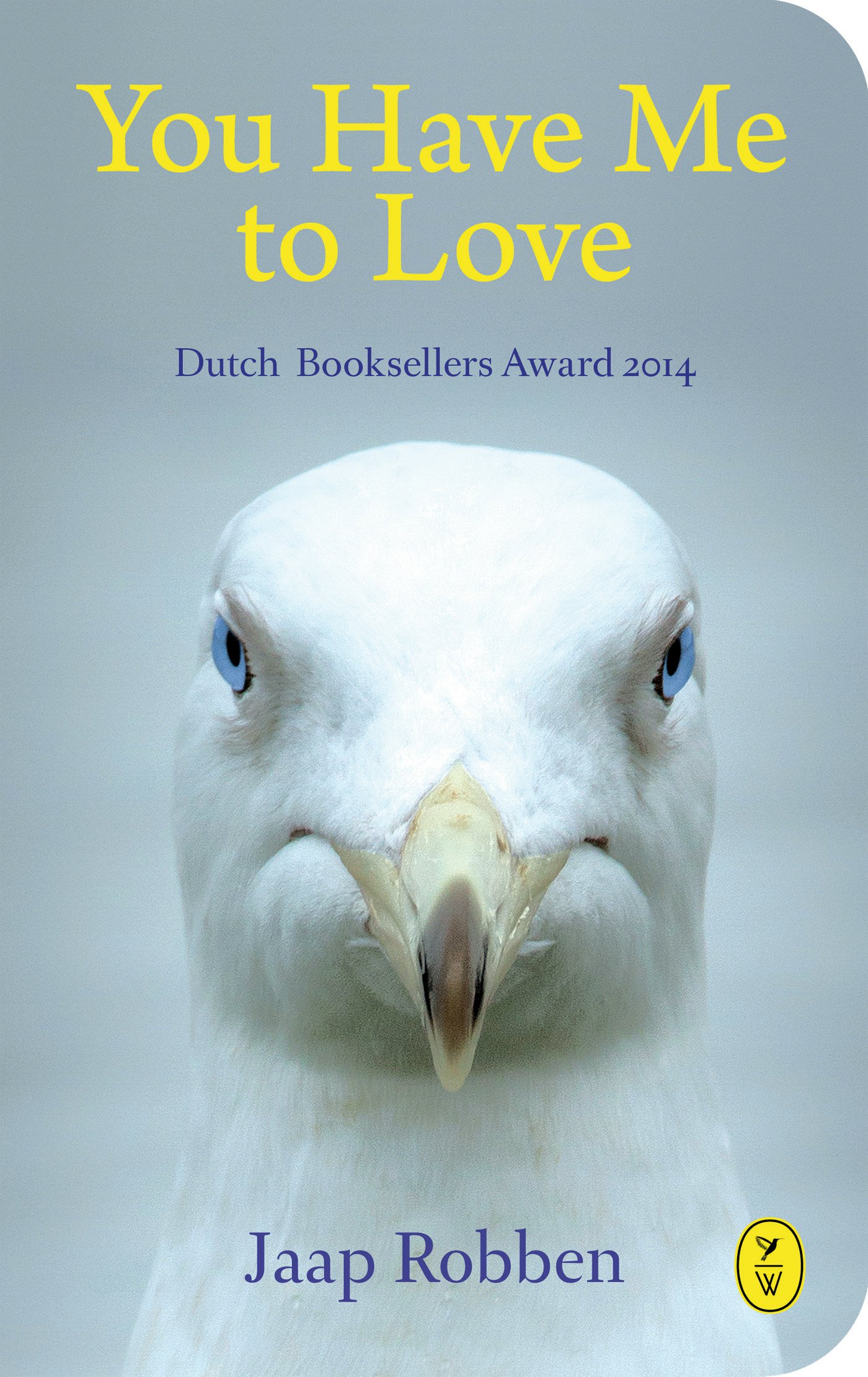

You Have Me to Love – Jaap Robben: a review for #BoekenweekUK

Welcome to the final stop on World Editions’ blog tour for Boekenweek, celebrating Dutch literature. Today I’m reviewing You Have Me to Love by Jaap Robben (translated by David Doherty). Robben is a poet, playwright and children’s author; Birk (to use the title of the Dutch version) is his first novel for adults. It won the 2014 Dutch Booksellers Away and the Dioraphte Prize. Having read the book, it’s not hard to see why.

Our narrator is young Mikael Hammermann, who lives with his parents, Dora and Birk, on an island somewhere between Scotland and Norway. There are only three houses on the island, and one of those is empty. Groceries arrive by boat every two weeks; Mikael is home-schooled, at least enough to do well in the tests that are sent to him periodically (and which he is allowed to complete in pencil, so they can be corrected before returning). Robben never places the island in a true geographical context, so throughout there’s a sense of dislocation which really comes into its own as the novel progresses.

The Hammermanns’ world is upended when, one day, Birk vanishes into the sea. The search for him yields nothing, though Mikael begins to see a tiny version of his father about the house – that is, until he’s forced to confront and reveal the full circumstances of Birk’s disappearance.

The rest of the novel chronicles life without Birk for mother and son. Dora’s attitude switches from blaming Mikael to something that he can’t quite read: for example, at one point Mikael’s mother announces abruptly that they’re going to swap bedrooms, ostensibly because he’s growing up and needs the bigger bed – but it still seems a strange thing to him. For his part, Mikael starts to help out the Hammermanns’ neighbour, Karl, with his fishing boat; though Dora is not keen, perhaps from a sense of possessiveness (for whom, is an open question). Mikael also attempts secretly to raise a gull chick in the island’s empty house, which is perhaps his way of proving himself to himself.

Jaap Robben

You Have Me to Love has a number of emotional turns that I wasn’t expecting – it’s really quite affecting. If you’d like a taste of the writing, Anne posted an extract from Doherty’s translation at Random Things Through My Letterbox yesterday. There’s also an animated short based on the book, which you can see here.

Book details

You Have Me to Love (2014) by Jaap Robben, tr. David Doherty (2016), World Editions, 256 pages, paperback (review copy).

Man Booker International Prize 2018: the longlist

Here we go! The shadow panel are ready, and yesterday the judges announced their longlist of thirteen titles:

- The 7th Function of Language by Laurent Binet, tr. Sam Taylor (France, Chatto & Windus).

- The Impostor by Javier Cercas, tr. Frank Wynne (Spain, MacLehose Press).

- Vernon Subutex 1 by Virginie Despentes, tr. Frank Wynne (France, MacLehose Press).

- Go, Went, Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck, tr. Susan Bernofsky (Germany, Portobello Books).

- The White Book by Han Kang, tr. Deborah Smith (South Korea, Portobello Books).

- Die, My Love by Ariana Harwicz, tr. Sarah Moses and Carolina Orloff (Argentina, Charco Press).

- The World Goes On by László Kraznahorhai, tr. John Bakti, Ottilie Mulzet and George Szirtes (Hungary, Tuskar Rock Press).

- Like a Falling Shadow by Antonio Muñoz Molina, tr. Camilo A. Ramirez (Spain, Tuskar Rock Press).

- The Flying Mountain by Christoph Ransmayr, tr. Simon Pare (Austria, Seagull Books).

- Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi, tr. Jonathan Wright (Iraq, Oneworld).

- Flights by Olga Tokarczuk, tr. Jennifer Croft (Poland, Fitzcarraldo Editions).

- The Stolen Bicycle by Wu Ming-Yi, tr. Darryl Sterk (Taiwan, Text Publishing).

- The Dinner Guest by Gabriela Ybarra, tr. Natasha Wimmer (Spain, Harvill Secker).

The titles above will turn to links as I review the books. To date, I have managed to read a grand total of one, Frankenstein in Baghdad, though I haven’t reviewed it yet (spoiler: it’s excellent). I have another six of them to hand, and have been looking forward to reading all of them. The books I don’t know also sound intriguing; this is going to be an exciting month-or-so of reading.

Recent Comments