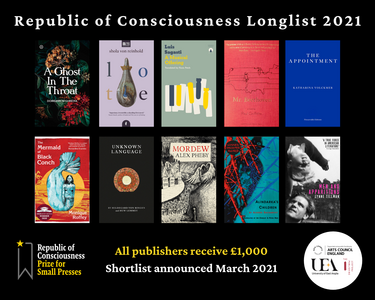

It’s that time of year again, when the International Booker Prize is almost with us (the longlist will be announced on Tuesday 30 March). Once again, I will be taking part in the Shadow Panel. We’ll be reading and reviewing the books, coming to our own conclusions about what’s good – and ultimately choosing our own shadow shortlist and winner.

This post is an introduction to the members of this year’s Shadow Panel. Without further ado, here they are:

***

Tony Malone (@tony_malone) is an occasional ESL teacher and full-time reader who has been publishing his half-baked thoughts on literature in translation at the Tony’s Reading List blog for just over twelve years now. One unexpected consequence of all this reading in translation has been the crafting of a few translations of his own, with English versions of works by classic German writers such as Eduard von Keyserling and Ricarda Huch appearing at his site. After a well-earned sabbatical year from all things shadowy, he’s returned with fresh energy in 2021, ready to discuss this year’s longlist and keep the ‘real’ judges honest.

Stu Allen (@stujallen), the everyman of translated fiction, has been blogging for twelve years and has reviewed over a thousand books from more than one hundred countries at his site, Winstonsdad’s Blog. He founded the original Shadow IFFP Jury back in 2012, as well as the Twitter hashtag #translationthurs. By day, he works for the NHS as a care support worker, helping people with learning disabilities on a ward in a learning disabilities hospitality centre in sunny Derbyshire. He’s married to Amanda, loves indie music, foreign films and real ale, and is pleased to be shadowing the prize for another year.

Meredith Smith (@bellezzamjs) has been writing about books at her site, Dolce Bellezza, since 2006. Now that she has retired from teaching, she has much more time to devote to her passion of reading translated literature. She has hosted the Japanese Literature Challenge for fourteen years and been a member of the Shadow Jury for seven. It is her great joy to read and discuss books from around the world with both the panel and fellow readers.

Oisin Harris (@literaryty), based in Canterbury in the UK, reviews books at the Literaryty blog. He earned an English degree from Sussex University and an MA in Publishing from Kingston University. He is a librarian at the University of Kent and a co-editor and contributor for The Publishing Post’s Books in Translation Team, as well as the creator of the Translator Spotlight series where prominent translators are interviewed to demystify the craft of translation. His work on Women in Translation was published in the 2020 research eBook of the Institute for Translation and Interpreting, entitled Translating Women: Activism in Action (edited by Olga Castro and Helen Vassallo).

Frances Evangelista (@nonsuchbook) works as an educator in Washington DC. She elected a career in teaching because she assumed it would provide her with lots of reading time. This was an incorrect assumption. However, she loves her work and still manages to read widely, remember the years she blogged about books fondly, chat up books on Twitter, and participate in lots of great shared reading experiences. This is her fourth year as a shadow panellist for the International Booker Prize.

Barbara Halla (@behalla63) is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote, where she has covered Albanian and French literature and the International Booker Prize. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of contemporary and classic Albanian women writers. She has lived in Cambridge (Massachusetts, USA), Paris, and Tirana.

Vivek Tejuja (@vivekisms) is a book blogger and reviewer from India, based in Mumbai. He loves to read books in Indian languages and translated editions of languages around the world (well, essentially world fiction, if that’s a thing). He is Culture Editor at Verve Magazine and blogs at The Hungry Reader. He is also the author of So Now You Know, a memoir of growing up gay in Mumbai in the 90s, published by Harper Collins India.

Areeb Ahmad (@Broke_Bookworm) recently finished an undergrad in English from the University of Delhi and is now pursuing a Master’s in the same subject from the University of Hyderabad. Although he is quite an eclectic bookworm, he swears by all things SFF. You can find him either desperately hunting for book deals to supplement his overflowing TBR pile or trying to figure out the best angle for his next #bookstagram picture while he scrambles to write a review. He impulsively decided to begin book blogging in 2019 and hasn’t looked back since.

And then there’s me…

David Hebblethwaite (@David_Heb) is a reader and reviewer originally from Yorkshire, UK. He started reading translated fiction seriously a few years ago, and now couldn’t imagine a bookish life without it. He writes about books at David’s Book World and on Instagram @davidsworldofbooks. This is his eighth year on the Shadow Jury, and it has become a highlight of his reading year. There are always interesting books to read, and illuminating discussions to be had.

***

So there we are. I’m not going to guess which books will be on the longlist, but whatever they are, I am sure it’s going to be another enjoyable year in the Shadow Panel. I hope you’ll join us for the journey.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recent Comments