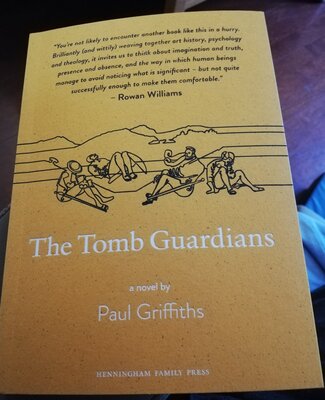

Henningham Family Press and Paul Griffiths were two of my favourite discoveries last year, and now here’s another beautifully produced book by the author of Mr. Beethoven. I was looking forward to The Tomb Guardians, but even so I wasn’t prepared for it.

When I look at my most favourite novels, it’s not about subject matter or subgenre – it’s about the reaction I have to reading them. The writing somehow bypasses the rational brain and affects me at a more fundamental level. The Tomb Guardians is that sort of novel.

Two conversations intertwine within the book. The first (in italics) is between the guardians of Christ’s tomb. They’ve woken up to find that the stone has been moved, the tomb is empty, and one of their number has also vanished. The guardians can’t work out exactly how all this happened, but they know they can’t admit to having been asleep. They have to concoct a plausible explanation that won’t land them in trouble.

In the present day, a lecturer is preparing a talk on the ‘sleeping grave guard’ paintings by the 16th-century German artist Bernhard Strigel [example], which are reproduced in the book as colour plates). The lecturer feels the talk is “falling apart”, and discusses it with a friend. The key question occupying the lecturer is: why doesn’t Strigel’s placid depiction of the guards reflect the Gospel of Matthew? The lecturer has some ideas about this: what if the figures are meant to reflect Strigel’s contemporary reality rather than the biblical one? What if they’re not meant to be the guardians of Christ’s tomb at all?

Both conversations then revolve around a fundamental absence of knowledge, though approached from opposite directions. The guardians are constructing a falsehood to explain away the empty tomb. The lecturer and friend are reaching for a truth about Strigel’s paintings that they’ll never fully grasp.

Maybe I’ve made The Tomb Guardians sound heavy so far, but actually it wears its seriousness lightly. The book is at its most playful when the conversations seem to talk to each other:

What?

It’s this lecture.

Yes.

I just don’t like it.

It’s falling apart on me.

There’s a lot I don’t like, beginning with that dirty great rock having shifted on its own-i-o.

That’s happened before.

He shouldn’t have gone.

Not like this. The whole point it’s…. Never mind.

No, he shouldn’t have gone.

It’s also interesting to see how the balance of the novel changes. The guardians feel dominant at the beginning, racing ahead to work their story out as the lecturer is hesitantly forming questions. Then the lecturer’s strand takes control, forging ahead with art-historical exploration, at times almost seeming as though it might be the guardians’ undoing.

The ending of The Tomb Guardians has the same sudden power as that of Convenience Store Woman, as we experience something of what is at stake for the characters. Griffiths’ novel doesn’t resolve, but stays vividly on the knife-edge of uncertainty. This undermines everything the lecturer has worked towards:

These four were my life. For years. And still there was so much I wanted to say to them. If they’d been here, I could have done that – never mind that they wouldn’t have been able to respond. I could have said they’re the only human beings right there, at exactly the right moment, and they’re missing the event. I could have said their sleep is an admonishment to us, who also sleep through so much….

But the lecturer’s friend sees how it is: you have to go on from where you are, even if there is doubt. For the guardians, meanwhile, there is possibility in the uncertainty as we leave them, and this opens the book up again just as we close it.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recent Comments