In his latest novel, Jeff VanderMeer brings us a mystery in which Detective John Finch — whose name is not John Finch, and who isn’t a detective (or so he keeps telling himself) — investigates a double murder. One of the victims is a man who can’t possibly be a murder victim, whilst the other is a gray cap—

In his latest novel, Jeff VanderMeer brings us a mystery in which Detective John Finch — whose name is not John Finch, and who isn’t a detective (or so he keeps telling himself) — investigates a double murder. One of the victims is a man who can’t possibly be a murder victim, whilst the other is a gray cap—

If the term ‘gray cap’ is unfamiliar (and even if it’s not!), welcome to Ambergris, the setting of VanderMeer’s City of Saints and Madmen (2003) and Shriek: an Afterword (2006), which, together with Finch, form a cycle of novels – though it’s not necessary to have read the previous two (and I’d say Finch makes a pretty good entry point). I am in the awkward position of remembering enough about City and Shriek that I didn’t come to the new book cold, whilst having forgotten enough that I know I missed some things in Finch, and can’t really give a proper assessment of the Ambergris Cycle as a whole. That’s where I started from, anyway.

Finch is set a hundred years after Shriek, at a time when Ambergris has been taken over by the gray caps, the inscrutable fungoid people who previously lived beneath the city. Spores that could do who-knows-what (or who-dares-imagine) to you proliferate, such that it’s a bad idea to go around barefoot, because you never know what you’ll step on. Some of the human population are held in camps, others kept docile with fungal drugs; but there are those who’ve their lot in with the gray caps to become half-human, half-mushroom ‘Partials’ – and there are rebels, led by the mysterious Lady in Blue, though she hasn’t been heard of for six years. And there are those like John Finch, a human in the employ of the gray caps, just trying to make their way through this world as best they can.

And these are difficult waters to navigate because, as in any good mystery, there are secrets, deceptions, and masks aplenty in Finch, not least those of the protagonist himself. ‘John Finch’ is an identity he created to hide that of the person he was before the Rising of the gray caps; and, despite his profession, Finch still doesn’t feel comfortable thinking of himself as a detective. To be fair, he doesn’t get very far with actual detecting in the novel, as most of the other characters seem to know more than he does, and are keen to reveal their knowledge to Finch only on their terms, not his. The motives and intentions of the gray caps are as mysterious as ever… all of this keeps the pages turning, no question.

Something else that keeps the pages turning is VanderMeer’s compelling prose. The style of an Ambergris story has always been significant, and Finch continues that trend. This novel is written in spiky, clipped prose that often gives an impression of restlessness, of wanting to get on to the next bit. For instance:

Inside, a tall, pale man stood halfway down the hall, staring into a doorway. Beyond him, a dark room. A worn bed. White sheets dull in the shadow. Didn’t look like anyone had slept there in months. Dusty floor…

This noir-inflected idiom is in sharp contrast to the lush, flowing styles I’ve associated with previous Ambergris books; but of course it’s entirely appropriate to the setting: Ambergris is a meaner, grimmer place than it was, so the voice that tells its stories naturally has a harder edge. VanderMeer’s writing is still vivid and striking (such as his idea of the ‘memory hole’, a revolting, organic way of delivering messages), but the colours of his palette are subtly different in Finch; for example, there’s more action this time around (or it’s more prominent than it was) – and it’s very effective action at that.

VanderMeer’s style in Finch also makes the telling feel more direct, which is something of a double-edged sword. On one hand, this novel is revealing things about the nature of Ambergris that the first two kept hidden, and the style plays into that aim. On the other hand, I can’t help feeling that some of the otherworldliness is lost, that some of these extraordinary revelations become a little too matter-of-fact in the telling. I also can’t help wondering if the pace is just that bit too brisk, resulting in a similar effect.

The characterisation of John Finch is another aspect about which I have reservations. In a very real sense, we don’t know Finch; and he’s often acted upon rather than being the actor himself. These can make it hard to see him as an individual, and I don’t think that VanderMeer always manages to overcome that. When he does, though, it makes for some powerful moments. For example, there’s the time when Finch is pleading with his lover, Sintra, to tell him something about herself – not out of idle curiosity, but because he’s desperate for something in his life to be real, and he wishes it were her. At times like this, one feels the burden of living in a world of secrecy.

In the end, then, I don’t think that Finch is entirely successful; but it is an interesting – and gripping – fusion of noir and fantasy. It takes unexpected turns, and ends at a point that may seem too early in some ways, but is actually quite appropriate – because it’s the point at which the story of Finch can no longer be told, and the style of Finch can no longer tell its story. But Jeff VanderMeer can go on telling his stories; and I hope he does, because they’re like no one else’s.

The well-known writer is

The well-known writer is  Nightjar’s second launch title is the beautifully harsh ‘The Safe Children’ by a young new writer named

Nightjar’s second launch title is the beautifully harsh ‘The Safe Children’ by a young new writer named  I have heard a lot about

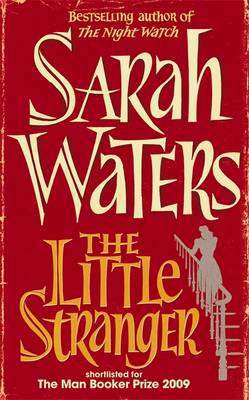

I have heard a lot about  The Little Stranger is my first

The Little Stranger is my first  Now up at The Zone is my review of

Now up at The Zone is my review of  In his début novel,

In his début novel,

Recent Comments