This review was first published at Splice in October 2018.

***

Meet Keiko Furukura. She has always found it difficult to conform to what her family and wider society consider “normal”. She once stopped a fight between a group of boys at primary school by hitting one of them over the head with a spade. She couldn’t understand what was wrong with this: “Everyone was saying to stop them, so that’s what I did,” she told her teachers. Throughout the rest of her childhood, Keiko kept her head down, saying no more than she had to — and the adults around her didn’t think that was normal, either. It wasn’t until she got a job at the Hiiromachi Station Smile Mart in 1998, whilst at university, that she felt she had finally found her place in the world. Eighteen years later, she’s still there.

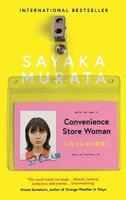

Convenience Store Woman is Sayaka Murata’s tenth novel, but the first to appear in English (translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori). The title may appear prosaic, but it points towards the essence of Keiko’s situation by combining place and person to suggest something greater than the sum of both. Keiko really does live and breathe her job. The store’s sounds reverberate through her head as she falls asleep at night, and she imagines the cells of her body energised at the prospect of being there. Those cells are also made up of food from the convenience store because that’s all Keiko eats, and the thought of this makes her “feel like I’m as much a part of the store as the magazine racks or the coffee machine.”

At heart, Murata’s novel is a challenge of empathy: a challenge for the reader to appreciate where Keiko, an individual considered unusual by many, is actually coming from. The opening scenes depict Keiko at the store and establish what she feels she has there. In training, Keiko likes the way that everyone looks the same in their uniform and has to say the same things: suddenly, everyone is equal. Rehearsing transactions with her fellow workers is like “playing at shop” and, since she’s good at mimicking what she has been taught, this is a game she can carry over into the job itself. The store, says Keiko, is the one place where she can be normal. She is a punctual and efficient employee, but it’s notable that, when a customer hesitates over an impulse buy, Keiko will hang back rather than step in and encourage them. This job is a role for her to play, and she can play it well, but it’s not a starring role — she doesn’t want to draw attention to herself.

Voice is a key aspect of Convenience Store Woman, because that is what creates and signifies changes to Keiko’s mental world. As befits her character, Keiko’s first-person narration is not particularly showy, but the perspective that results from it is nevertheless distinctive. Keiko refers to the store as an “aquarium” or “light-filled box”, highlighting (unwittingly) its enclosed nature. She also regularly comments that she has to keep her body fit for work at the store; by repeating these words and phrases, Keiko underscores how bound she really is to her workplace.

When she’s with other people, Keiko will typically copy their style of speech. At the store, she draws surreptitiously on her co-workers:

My present self is formed almost completely of the people around me. I am currently made up of 30 percent Mrs. Izumi, 30 percent Sugawara, 20 percent the manager, and the rest absorbed from past colleagues such as Sasaki, who left six months ago, and Okasaki, who was our supervisor until a year ago.

It’s not only speech that Keiko mimics, either. Mrs. Izumi dresses like Keiko’s idea of a “normal” thirtysomething woman, so Keiko has started to shop in the same places and wear similar brands — but not exactly the same clothes, because that might draw too much attention to her mimickry. In her downtime, though, Keiko’s friends have noticed the changes in how she dresses and talks; essentially, she is wearing a costume outside of work as well as in. “It was the me with different clothes and speech rhythms that was smiling,” she comments. “Who was it that my friends were talking to?” Yet, intriguingly, it’s not only Keiko who seems to be playing a role. Her friends’ conversation often comes across as generic — “Everyone should bring their husbands and kids too. Let’s have another barbecue!” — as expressions of another idea of what’s “normal”. But their normal is the social default, which gives it a certain authority. When they ask Keiko if she’s going to get married or have children, the pressure she feels to conform is genuine.

So Keiko has her nicely ordered world, which is just about holding together the way she prefers it, and then along comes Shiraha, the person who turns it all upside down. It’s immediately clear that Shiraha does not fit in at the store: he speaks and acts differently from the other staff. When he arrives for his first day at work, his response to the manager’s energetic patter and Keiko’s upbeat (though rehearsed) greeting is a series of ‘ums’ and ‘okays’. He doesn’t get along with the idea of everyone saying the same lines to customers, commenting that “it’s just like a religion”. Keiko’s silent riposte is: “Of course it is” — the conformity that Shiraha detests is an anchor for her.

Ultimately, Shiraha proves to be a slacker and a creep, even attempting to find the home address of one of the store’s customers. It’s no surprise that he is soon fired, and the change that Keiko notices in the way her colleagues talk once he has left underlines that he was a disruptive force to the order that Keiko values: “For all that [the staff] were complaining [about Shiraha’s behaviour], somehow there was an air of relief in the store”, she says, “[a]nd everyone had become strangely cheerful and chatty, as if refreshed now that the nuisance had gone.” But what this passage also suggests is that Keiko is missing some of the nuances in her fellow-workers’ reactions. She can understand how they are feeling, and she can take a guess at why, but her logical awareness of their feelings comes as a surprise to her; she herself doesn’t feel anything similar. This is why Shiraha represents such a challenge to the stability of Keiko’s world: he disturbs the emotional patterns to which she has become accustomed. During Shiraha’s first day, a colleague compliments Keiko on never losing her cool, but Keiko takes this as an accusation of being a fake and she feels she has to come up with a suitable explanation: “I just don’t let it show.” The dispassion which has helped carry Keiko through the job so far is suddenly drawn into question when Shiraha enters the equation.

But Shiraha’s involvement in Keiko’s life does not end there: it becomes the driving force of the novel’s second half. Keiko finds Shiraha outside the store one night, some time after his firing, starts talking to him, and, not wishing to be seen by customers, suggests they pop into a nearby restaurant. Their conversation follows the same broad pattern throughout: Shiraha spouts his opinions, and Keiko weighs him up. For example, at one point, Shiraha moans about being stuck in casual work and not having a girlfriend, and egregiously compares being laughed at to being raped. This is Keiko’s reaction:

I considered him one step short of being a sex offender, but here he was casually likening his own suffering to sexual assault without sparing a thought for all the trouble he’d caused for women store workers and customers. He seemed to have this odd circuitry in his mind that allowed him to see himself only as the victim and never the perpetrator, I thought as I watched him.

In this passage, and perhaps for the first time, Keiko views someone else as an outsider, analysing his differences in a way that others may analyse hers. She feels as out of step with society’s expectations as Shiraha does, but Shiraha is angry whereas Keiko is detached, dispassionate, and that’s what prompts her to evaluate him during their meeting. She comes to see how they might be useful to each other: Shiraha could do with a semblance of normality in his life to get society off his case, and Keiko feels under pressure to make a change — so why don’t they live together?

Shiraha ends up moving into Keiko’s bathroom and spends much of his time berating her for, as he sees it, wasting her life in a low-paid job — in other words, for being so similar to him. Keiko, for her part, often describes their arrangement in terms of keeping a pet; if Shiraha is taking advantage of her goodwill, Keiko doesn’t seem bothered. It isn’t exactly a relationship.

The outside world does not see it that way, however, and here is where Keiko’s familiar existence really starts to crumble. For one thing, the differences between Keiko and the other convenience store workers are cast into sharp relief. Having always thought that putting on the uniform made everyone the same, Keiko is “shocked” at the way her manager and colleague respond to her news about Shiraha:

I couldn’t believe they were putting gossip about store workers before a promotion in which chicken skewers that usually sold at 130 yen were to be put on sale at 110 yen. What on earth had happened to the pair of them?

Keiko feels the store’s character changing, and she doesn’t like it. Shiraha’s presence also breaks apart the generic chatter of Keiko’s family and friends. When her sister sees how Keiko is living, she is driven to get direct with her: “The way you talk, the way you yell out at home as if you were still in the store, and even your facial expressions are weird. I’m begging you. Please try to be normal!” All these upheavals in Keiko’s world lead her to take the ultimate step: she quits her job at the store. But this throws her life even more off-balance: now that she doesn’t need to keep her body fit for work, she feels no motivation to eat healthily. Where she used to fall asleep with the sounds of the store in her ears, now there is only silence.

On the day of Keiko’s first interview for a new job — that is, the first day on which she might take a definitive step away from her old life — she pops into a convenience store to use the toilet. Instinct kicks in: Keiko can’t help but move the stock around and tell the staff what they should do to make the store better. Shiraha and Keiko both thought of the Smile Mart’s conformity as a religion, and this is a religious experience for Keiko now:

I couldn’t stop hearing the store telling me what it wanted to be, what it needed. It was all flowing into me. It wasn’t me speaking. It was the store. I was just channeling its revelations from on high.

This whole scene erupts from the page in a rush of pure joy, even though it’s narrated in much the same tone as the rest of the book, because one senses that Keiko is in her element as never before. Even though she worked at the convenience store for eighteen years, there was always an element of doubt: Keiko was essentially playing a part, which brought with it the possibility that the part wasn’t really her. It takes the loss of that touchstone in her life for Keiko to realise that she is a convenience store woman after all.

As readers, thanks to Keiko’s characterisation, and Murata and Takemori’s affectless prose, we are able to feel out the contours of Keiko’s world, anticipate potential threats to its equilibrium, and understand why it falls apart when Shiraha arrives. The setup for Keiko’s dilemma, throughout Convenience Store Woman, is never less than engaging, but that final convenience store scene is very special indeed. It’s not necessarily that we come to think like Keiko, but Murata enables us to empathise with her so deeply that we can perceive what Keiko’s epiphany means for her in a way that perhaps even she herself cannot. This crowning moment makes for a superb reading experience, and real insight into a character who doesn’t really let people see what is happening inside her at all.

***

Convenience Store Woman is published by Granta Books.

Recent Comments