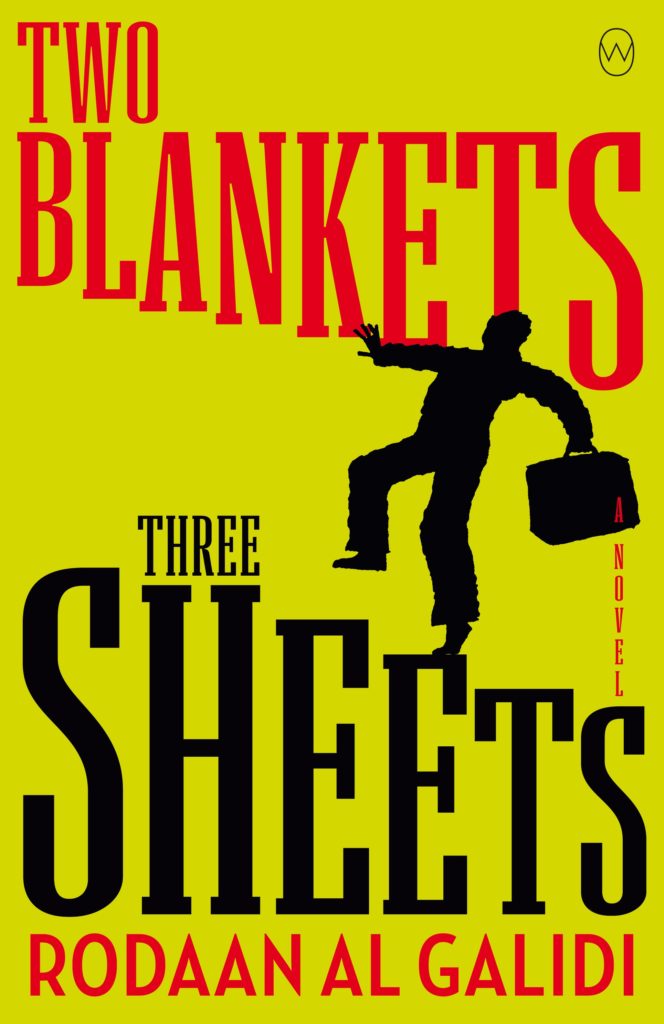

It’s time for my second stop on the UK blog tour for Boekenweek. Today I have an extract from Two Blankets, Three Sheets by Rodaan Al Galidi, translated from the Dutch by Jonathan Reeder and published by World Editions.

The blurb goes like this:

Amsterdam Airport, 1998. Samir Karim steps off a plane from Vietnam, flushes his fake passport down the toilet, and requests asylum. Fleeing Iraq to avoid conscription into Saddam Hussein’s army, he has spent seven years anonymously wandering through Asia. Now, safely in the heart of Europe, he is sent to an asylum center and assigned a bed in a shared dorm—where he will spend the next nine years. As he navigates his way around the absurdities of Dutch bureaucracy, Samir tries his best to get along with his 500 new housemates. Told with compassion and a unique sense of humor, this is an inspiring tale of survival, a close-up view into the hidden world of refugees and human smugglers, and a sobering reflection of our times.

An extract from the novel follows next…

Rodaan Al-Galidi spent nine years in an Asylum Centre in the Netherlands before he finally obtained Dutch citizenship as part of a General Amnesty. Two Blankets, Three Sheets, published by World Editions, is narrated by ‘Samir’, but is based on Rodaan’s story.

Here he describes how he first lands in Netherlands and prepares to claim asylum.

I landed at Schiphol Airport at 9 a.m. on the eleventh of February. Or at 11 a.m. on the ninth of February, I can’t remember the exact date anymore. I do know that it was 1998.

Some twenty hours earlier I had been walking around Ho Chi Minh City Airport with my forged Dutch passport. The photo had been well-doctored, but there was one hitch: the height of the official owner was 1.73 meters. I am 1.86—thirteen centimetres, almost half a foot, taller. The hand that now writes these words trembled as I stood in line at customs. I could not convince the hand that if its trembling betrayed me, it could mean years in a Vietnamese jail. When it was my turn, I handed the passport, which also trembled, to the customs agent. His narrow Asian eyes bored into me. He examined my passport, looked up and asked, in English: “Where is Curaçao?” His question took me by surprise. I had memorized the information in the passport, spent hours practicing the signature. I knew that its bearer was born in Curaçao, but where that was, I did not know, nor had it struck me as something I should know. The man looked at me, waiting for an answer.

“Near Amsterdam,” I said nervously. The man squinted. “About forty kilometres northeast of Amsterdam,” I added quickly, feeling the need to provide more details. “A pretty place.” Then he smiled. His curiosity had been satisfied, and he stamped the passport.

Landing in the Netherlands gave me my first glimpse of Europe, the origin of all those marvellous books whose translations I spent so much effort tracking down in Iraq, and which I then devoured. Europe might be grey outside, but to me it was more beautiful than any other country I had ever seen. I looked out the airplane window and considered that, for the first time in my life, I could be a person. Here I would shed my fear like an old, torn pair of trousers. Here I would discard my caution like smelly, holey socks. I will never forget that blissful feeling. I waited in my seat until everyone else had disembarked past the smiling Asian stewardesses. As I walked to the aircraft door, I prayed the immigration officials wouldn’t be carrying out spot checks, because then they would see where I had come from and send me straight back. Luckily I made it unhindered through the jetway and into the transit hall, where I was relieved to quickly vanish among the other travellers. Some had just arrived, some were just beginning their journey, and others were merely passing through. As for myself, I wasn’t sure whether I had arrived, or was beginning my journey, or passing through. First things first: the China Airlines plane had to take off again, and leave Schiphol without me.

Normally a passport is one’s most precious possession in a transit hall, but mine was my greatest liability. I had to get rid of it as quickly as possible. If the police catch you with a forged passport, they know which airplane you arrived on, which means they also know how to deport you.

I was a bundle of nerves when a policeman approached me and asked if I needed assistance. “Toilet,” I said in English, and crossed my legs so he would see that I wasn’t acting strangely out of anxiety but out of physical necessity. He pointed to the nearest men’s room and I thanked him. Once out of sight, I went the other way and ducked into one further up instead. There I tore my passport and ticket into the tiniest possible scraps and dropped them into the toilet bowl. I did the same with the addresses I still had with me, as well as all my Thai, Vietnamese, Laotian, and Malaysian banknotes.

I flushed the global trail that had led me to Schiphol down the toilet. I also threw away the Asian souvenirs I had bought on the advice of a smuggler in Bangkok, who said that travellers to Europe without hand baggage attract attention at the airport, because Europeans always buy souvenirs. So I had filled a carry-on bag with gifts purchased here and there from sidewalk peddlers. The smuggler was right: after checking my bag at Ho Chi Minh City, they zipped it shut with a smile because I had such good taste. Once back outside the men’s room all I had on me was ten dollars.

The only thing I regretted was having neglected to bring any warm clothing. I was so busy avoiding getting caught that I didn’t consider what kind of clothes would be useful in Holland. In fact, I hadn’t the slightest idea of the climate here. Wearing nothing but a t-shirt, I walked through the transit hall and marvelled at its enormity. It resembled a city, where everything you wanted could be had.

After an hour had passed, and the China Airlines plane had taken off again, I felt the ten dollars burning a hole in my pocket. Should I drink a nice cup of hot tea, eat a Big Mac, or phone my mother? The photo of the Big Mac made my Adam’s apple move up and down, but when I saw people drinking tea, that seemed to me a tastier choice. In the end I decided to call my mother to reassure her. As though I had just left the house that morning, and not seven years earlier.

As far as my mother was concerned, everywhere in the world was safe and wonderful, except Iraq. I don’t know where she acquired this positive image of the world, because when I once asked her how old she was— we don’t know each other’s birthdays—her answer was: “Eight wars.”

“I mean in years, mother.”

I hadn’t spoken to her in more than a year and she had no idea where I was all that time, but when I got her on the line it felt as though I was calling from a block away to say I’d be bringing friends around for dinner. I said I was greeting her from the Netherlands. My mother is illiterate, but she did know that Dutch cows produce lots of milk. In Iraq, Dutch cows have a better reputation than Rembrandt.

“Oh, thank God—Holland,” my mother said. “God loves the Dutch, why else would he have made their cows’ udders so big? There, among all those cows, you won’t go hungry, Samir.” I pressed the receiver tightly against my ear to hear her voice better. “Do you remember our Dutch cow? She gave enough milk a day for twenty people.” She went on to tell me what had become of the cow, until I was down to my last cent and we got cut off.

About the author

Rodaan Al Galidi is a poet and writer. Born in Iraq and trained as a civil engineer, he has lived in the Netherlands since 1998. As an undocumented asylum seeker he did not have the right to attend language classes, so he taught himself to read and write Dutch. His novel De autist en de postduif (‘The Autist and the Carrier Pigeon’) won the European Union Prize for Literature in 2011—the same year he failed his Dutch citizenship course. How I Found the Talent for Living, already a bestseller in the Netherlands, is his most successful novel to date.

About the translator

Jonathan Reeder, a native of New York and longtime resident of Amsterdam, enjoys a dual career as a literary translator and performing musician. Alongside his work as a professional bassoonist he translates opera libretti and essays on classical music, as well as contemporary Dutch fiction by authors including Peter Buwalda, Bram Dehouck, Christine Otten, Adri van der Heijden, and Two Blankets, Three Sheets by Rodaan Al Galidi. His recent translations include Rivers by Martin Michael Driessen (winner of the 2016 ECI Literature Prize) and The Lonely Funeral by Maarten Inghels and F. Starik.

***

Thanks to World Editions and Ruth Killick Publicity for the extract.

Yesterday the #Boekenweek2020 UK blog tour stopped at Linda’s Book Bag. It continues tomorrow at Lizzy’s Literary Life, with further stops to come at Trip Fiction and Winston’s Dad. The tour finishes on Sunday.

Recent Comments