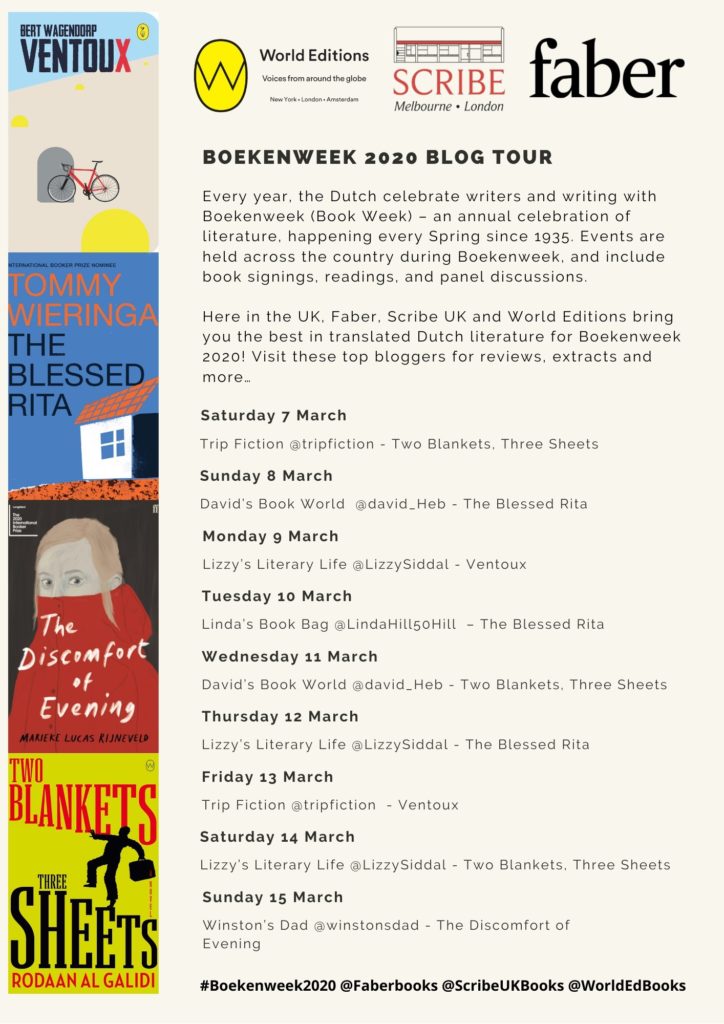

Today’s post is part of a UK blog tour to mark Boekenweek, an annual celebration of Dutch literature that takes place each spring in the Netherlands.

I’m pleased to share an extract from The Blessed Rita, the latest novel by Tommy Wieringa to appear in English, translated by Sam Garrett. I was impressed by Wieringa’s The Death of Murat Idrissi last year, so I’m looking forward to this one.

Here’s the blurb:

What is the purpose of a man? Living in a disused farmhouse with his elderly father, Paul Krüzen is not sure he knows anymore. The mill his grandfather toiled in is closed, the glory of the Great Wars is long past, and it has been many years since his mother escaped in the arms of a Russian pilot, never once looking back. What do they have to look forward to now?

Saint Rita, the patron saint of lost causes, watches over Paul and his best friend Horseradish Hedwig, two misfits at odds with the modern world, while Paul takes comfort in his own Blessed Rita, a prostitute from Quezon. But even she cannot protect them from the tragedy that is about to unfold.

In this darkly funny novel about life on the margins of society, Dutch sensation Tommy Wieringa asks what happens to those left behind.

If that’s piqued your interest, here is an extract from the book…

From The Blessed Rita by Tommy Wieringa (translated from the Dutch by Sam Garrett).

Paul Krüzen’s mother was a daughter of the last blacksmith in the village. His smithy had been across from the church, at the start of Bunderweg, where later, during the construction goldrush, a white- stone insurance office would arise. The smith’s name was Mans Klein Haarhuis and he was tawny as a Sicilian fisherman, but his two daughters were creamy-white children of Mariënveen. His son Gerard, the youngest, looked like him though: stocky, and with a head of dark, wavy hair.

It was the Klein Haarhuis sisters who were biking along Bunderweg to Kloosterzand on that cloudy day in 1955. Marion and Alice crossed the little bridge over the Molenbeek and did not notice the boy sitting beside the stream, listening to their cheerful twittering. Once they were past the bridge, he climbed onto the road and watched until they disappeared from sight. From along the banks he quickly picked all the flowers he could find — irises, cowslips, and a few final spikes of seeding elderflower — and placed the bouquet on the road when he saw them coming back in the distance. Then he hid behind a tree, his heart pounding. Just as they reached the bridge, a fire-engine red McCormick roared past — the girls could barely maintain their balance and hissed indignantly at the machine.

Aloïs Krüzen was twenty-six when he married Alice Klein Haarhuis. Round, blushing, and in the blossom of late youth, she stepped across the grey paving stones to the altar, arm-in-arm with the smith in his Sunday best, his greying curls held in sway at the last moment with Brylcreem. Square and grim, he was on the verge of giving away the loveliest thing he possessed. Her clearly audible, sing-songy ‘I do’ a few minutes later broke, with equal clarity, a few of the hearts present in the church. The fait accompli — she had vanished through the door ironclad by the sacrament, and all they had left to hope for was the breach.

It was a miracle that Alice Klein Haarhuis had fallen for Aloïs Krüzen, and only because, as people said, she refused to marry a farmer. Aloïs had gone to teacher’s college in town and returned a schoolmaster. A man with an indoor job and a fixed income, how much better could it get? That was how Aloïs Krüzen got his bride, and no one could help but feel that it was cheating.

***

They went on honeymoon in his father-in-law’s car, the first automatic in the village, a brand-spanking-new, 2.6-litre Opel Kapitän; Mans Klein Haarhuis had walked around Aloïs’ Lloyd Alexander TS a few weeks earlier and said: ‘You can’t take your lassie away in that …’

They skimmed down the road like a canoe through water, six cylinders working in silence. Her hand lay on his thigh, as still as though she’d forgotten it. The low sky was of graphite, green as the first day on earth.

After they had crossed the IJssel at Zutphen, the landscape changed. Dark rises on the horizon, where the old ice had left moraines. Rivers of lead snaked across the low land. The further south they ventured, the heavier the stone on Aloïs’ chest became. The horror that awaited them — the frontal collision that would crush them, their blood mixed with oil on the asphalt …

Him counting his blessings — a magnificent girl beside him, a bag full of money, and an automatic at his fingertips — didn’t help in the slightest: the feeling was under his skin.

‘Still, it’s further than I thought,’ Alice said absently. She stared out the window.

‘Always is,’ he said. The stone pressed down. Keep the wheel straight, drive defensively, know that you can never escape from yourself.

About the author

Tommy Wieringa was born in 1967 and grew up partly in the Netherlands, and partly in the tropics. He began his writing career with travel stories and journalism, and is the author of several internationally bestselling novels. His fiction has been longlisted for the Booker International Prize, shortlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and the Oxford/Weidenfeld Prize, and has won Holland’s Libris Literature Prize.

About the translator

Sam Garrett has translated some fifty novels and works of nonfiction. He has won prizes and appeared on shortlists for some of the world’s most prestigious literary awards, and is the only translator to have twice won the British Society of Authors’ Vondel Prize for Dutch–English translation.

***

Thanks to Scribe Publications UK and Ruth Killick Publicity for the extract. The Blessed Rita is published by Scribe UK on Thursday 12 March.

The #Boekenweek2020 UK blog tour began yesterday at Trip Fiction and continues tomorrow at Lizzy’s Literary Life. I’ll have another extract up on the blog this Wednesday.

Recent Comments