I like to follow the Republic of Consciousness Prize for Small Presses, because I’m interested in the kind of fiction it stands for, and it’s good for highlighting worthwhile books that I might otherwise miss. Sue Rainsford’s debut novel, from the Irish publisher New Island Books, is one of those. It caught my interest on this year’s Republic of Consciousness longlist, and when I saw Daniel Davis Wood of Splice compare it on Twitter to The Man Who Stole Attila’s Horse by Ivan Répila, that was enough to convince me to read Follow Me to Ground.

Now that I’ve read both books, I agree with Daniel’s comparison: Rainsford’s novel has the same sense as Répila’s of taking place in its own bubble of reality, and I could even imagine it as a stylised animated film, like Attila’s Horse. Rainsford’s narrator is Ada, who lives with her father in a village whose inhabitants (which they call “Cures”) come to them for healing. Despite appearances, Ada and Father are not exactly human. Father can be positively animalistic:

There were nights when he’d let his spine loosen and go running on all fours through the woods, leaving sense and speech behind.

Ada doesn’t partake in that behaviour, but both she and Father were born in “the Ground”, the lawn of their house, which has mysterious properties and almost a mind of its own. Father has tamed a section of the Ground which they use to bury those Cures who require more intensive healing. Even their most straightforward curative techniques appear strange to our eyes:

Claudia Levine arrived at noon and I sang her belly open, sang her sickness away – tricked it into a little bowl under the table. Closed her up again, woke her up again. Told her she’d be sore in the morning, waved her away down the drive, poured her sickness down the drain.

The way Ada describes herself and Father, we never get a firm handle on exactly what they are or what they do. The net effect of this is to create a sense of mystery at the novel’s heart which gnaws away at the reader.

I once read an annoying story by China Miéville about magical playing cards, which essentially used evocative names (such as “the Four of Chimneys”) in lieu of revealing anything concrete about what these cards actually did. This technique didn’t work for me, because it just highlighted how arbitrary the whole thing was – to me, there was simply nothing behind the names. I find that Rainsford’s approach works much better: she reveals enough of Ada’s world to catch the imagination, but not so much as to much as to define it. The mystery remains alive.

Ada is in love with a Cure named Samson, and her relationship with him becomes central to Follow Me to Ground. She grows increasingly possessive of him, in the face of disapproval from both Father and Olivia, Samson’s sister. Here is where the novel’s approach really comes into its own, because the obsession gnawing away at Ada mirrors the reader’s sense of ungraspable strangeness. And (without wishing to say too much) the matter of what ultimately happens is driven by that same sense of unresolved mystery. I’m glad to have found Follow Me to Ground through the Republic of Consciousness Prize; I’ll be looking out for more of Sue Rainsford’s work, too.

Book details

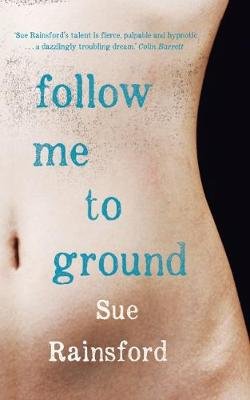

Follow Me to Ground (2018) by Sue Rainsford, New Island Books, 204 pages, hardback (source: personal copy).

15th February 2019 at 10:32 am

Attila’s Horse was an interesting and unconventional novel, so this one sounds promising – especially as it takes a woman’s (or female’s!) perspective

9th May 2019 at 8:35 pm

I think if you liked one book, you’ll probably like the other, different as they are.

17th February 2019 at 6:55 pm

The Boy Who Stole Attila’s Horse remains one of my favourite books so your review has got me very interested in this. I’ve also found, over the years, that prize lists can be a great way of discovering new authors.

9th May 2019 at 8:34 pm

The Republic of Consciousness Prize is especially good for discoveries. I like that it can still surprise me, even though I’m pretty clued up when it comes to small press fiction.