One thing that really struck me about Human Acts, Han Kang’s novel of the Gwangju Uprising, was how it made violence pervasive but incomprehensible: there is large-scale brutality in the background (and sometimes in the foreground), but the most powerful images for me are the small human movements, because that’s the level at which we can process what is happening. I was reminded of this when reading Faruk Šehić’s debut novel Quiet Flows the Una, which deals with the Bosnian War; because it creates a similar sense of an event that cannot be comprehended within a conventional novelistic frame.

One thing that really struck me about Human Acts, Han Kang’s novel of the Gwangju Uprising, was how it made violence pervasive but incomprehensible: there is large-scale brutality in the background (and sometimes in the foreground), but the most powerful images for me are the small human movements, because that’s the level at which we can process what is happening. I was reminded of this when reading Faruk Šehić’s debut novel Quiet Flows the Una, which deals with the Bosnian War; because it creates a similar sense of an event that cannot be comprehended within a conventional novelistic frame.

Šehić’s narrator – who is probably named Mustafa Husar (“Sometimes I’m not me,” he says), and might be an analogue for the author – grew up in the town of Bosanska Krupa, whose river is bound into the very fabric of local life:

Our town grew out of people’s bond with the river. The Una is the power that holds the town together, otherwise both the river and its people would have been swept away long ago; like tortoises with houses on their backs, they would have fled far and wide. They know very well that problems vanish by simply watching the flow of the river.

(Translated from the Bosnian by Will Firth.)

Mustafa fought in the war, an experience that still troubles him deeply (“Don’t ask me who I am,” he tells us, “because that scares me”). The pretext of Quiet Flows the Una is that he goes to see a visiting circus with some old comrades, and ends up as the hypnotist’s volunteer; the novel’s chapters are the memories that Mustafa relives. They come at random, from youth and adulthood, wartime and after. The Una flows through it all, touched by conflict but ultimately surviving:

The river flowed as if nothing had changed. Three metres beneath the surface, in the heart of a greenhole, the silence was inviolable. The fish went about their miracles, and the acoustic impressions of an artillery attack on the dot of noon don’t reach them. The forces of nature are insensitive to wartime operations. The tree breaks in half when hit by a tank shell. It has no words to complain with.

Mustafa is quick to point out is that analysis after the fact does not capture the lived experience of war: “I wasn’t a tiny cog in the workings of some cosmic powers – as a real man with a formed personality, I had one private mission: physical survival.” But, with the world he knew slipping away, our narrator also wants to keep it alive somehow, perhaps by describing things in great detail:

I hoped this act of description would make my objects firm and indestructible in the world that surrounded me like an endless dark forest. Everything that was gone forever could be rebuilt with words, I thought…But the loss of the pre-war world of emotions and the palpable objects that comprised it – living rooms (the universe of the intimate), books (time machines) and photographs (time conserved in crystal) – was manifested for me as extreme pain.

So Mustafa’s next thought is to write a book – the book in our hands. “Writing would allow me to make myself a crutch, a substitute world.” Here, Šehić – like Han Kang in Human Acts – makes the problem of writing about his subject part of the text itself. Fiction can’t capture the true reality of war, this novel suggests; but it can create a proxy in words, a space to confront something of that reality. The broken chronology of Quiet Flows the Una reflects an event and an experience which can only be glimpsed In flashes and fragments. But those glimpses are vital, in multiple senses of that word.

Elsewhere

- An excerpt from the novel at B O D Y.

- The book’s publisher page at Istros Books.

- Reviews of Quiet Flows the Una at roughghosts (by Joseph Schreiber); European Literature Network (by Anna Blasiak); and the Irish Times (by Eileen Battersby).

Book details (Foyles affiliate link)

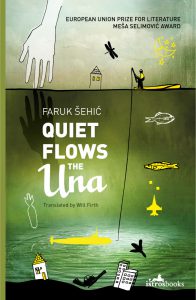

Quiet Flows the Una (2011) by Faruk Šehić, tr. Will Firth (2016), Istros Books paperback

Recent Comments