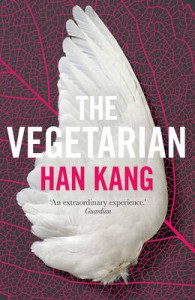

When you shake off the hundred-plus books of a year’s reading and find that the one clings the longest is the one you read first, chances are that it’s a special book. Han Kang’s The Vegetarian was exactly that, so you can imagine how much I was looking forward to reading Human Acts, her latest book to appear in English (like its predecessor, translated superbly from the Korean by Deborah Smith). The new novel is just as powerful (If not more) as I could have hoped; but it also makes for an interesting thematic comparison with the earlier one.

When you shake off the hundred-plus books of a year’s reading and find that the one clings the longest is the one you read first, chances are that it’s a special book. Han Kang’s The Vegetarian was exactly that, so you can imagine how much I was looking forward to reading Human Acts, her latest book to appear in English (like its predecessor, translated superbly from the Korean by Deborah Smith). The new novel is just as powerful (If not more) as I could have hoped; but it also makes for an interesting thematic comparison with the earlier one.

The Vegetarian explored themes of personal control, the body, the larger ramifications of individual actions – but within the context of a scenario that was clearly exaggerated and artificial. Human Acts has a similar approach, but it revolves around a real event: the Gwangju Uprising of 1980, in which students and factory workers demonstrated against the ruling dictatorship, and were brutally suppressed. The fact of that reality – how to deal with it, how to write it – is the black hole that sits at the heart of this novel.

Each chapter is written from the viewpoint of a different character, but the main link between them is the subject of the first: Dong-ho, a boy who goes to the gymnasium being used as a makeshift morgue in order to find the body of his friend, and ends up becoming one of the volunteers handling all the corpses. One thing that particularly struck me on reading Human Acts was that the smallest things were often the most powerful – such as this from the opening chapter:

A thin scream rang out several times from the top of the road, and three soldiers carrying guns and clubs raced down over the hilltop, surrounding the young couple. They looked to have been pursuing someone, and to have turned down this alley by mistake.

‘What’s the matter? We’re just on our way to church . . .’

Before the man in the suit had finished speaking, you saw a person’s arm – what? Something you wouldn’t have thought it capable of. Too much to process – what you saw happen to that hand, that back, that leg. A human being. (p. 26)

That first chapter has no shortage of specific detail of violence and the gruesome drudgery of dealing with so many bodies and coffins; but what most hit home was this moment of incomprehension, in which people can only be seen as abstract body parts. I’m grateful to Melissa Harrison for helping me clarify my thoughts on this, when she suggested on Twitter that Human Acts embodies the way one’s brain tries and fails to grasp what is happening. I think she’s right: the horror is right there in front of us, but so vast that it almost becomes background noise – and so it is the smaller moments that leap out, such as an involuntary somersault, or the seven slaps to the face which one character spends her chapter trying to forget.

So much in Human Acts comes back to bodies, not just as repositories of sensation, but also as markers of identity. In one chapter, the spirit of Dong-ho’s friend hovers around his old body as it festers among others in a pile. “Without bodies, how would we know each other?” he asks. “Would I still recognise my sister as a shadow?” (p. 55). Elsewhere, the body becomes a battleground: one chapter describes the torture of a prisoner, who realises that the brutal treatment being meted out to him and his fellow captives is meant to make them believe they are “nothing but filthy stinking bodies” (p. 126). A few pages earlier, however, he describes what it was like to be in the uprising, among the crowd facing the soldiers:

I felt the blood of a hundred thousand hearts surging together into one enormous artery, fresh and clean . . . the sublime enormity of a single heart, pulsing blood through that vessel and into my own. I dared to feel a part of it. (p. 121)

A body could be the lowest thing of all, but also something greater; it all depends on perception. The struggle for that perception – that meaning – is, it seems to be, underneath all that happens in the novel.

At the end of the book, Han tells of how she came to write Human Acts; by framing this as an epilogue, she brings the problem of writing about the Gwangju Uprising into the fiction itself. We can see echoes in the novel of Han’s experiences as narrated in the epilogue: for example, she was a young child in Gwangju at the time of the uprising, and her first encounters with the event are overheard snippets of adult conversation; likewise, the reader’s view is largely ground-level and piecemeal. But the question remains for Han: how can this event be treated most appropriately in fiction? Rather than zooming out and trying to encompass the uprising in a novel, she focuses in on its component parts – the individual human acts that make up even the largest swathes of history.

Now read on…

Naomi from The Writes of Woman, and Eric from Lonesome Reader, both have fine reviews of Human Acts on their blogs. You can also read an extract from the novel over at Bookanista.

Book details (Foyles affiliate link)

Human Acts (2014) by Han Kang, tr. Deborah Smith (2016), Portobello Books paperback

Recent Comments